Charles R. Knight's most famous painting. From Norman Felchle, via flickr.

There's really no other way to wrap up this week than with Charles R. Knight, one of the three early giants of paleoart and probably the best known. His work is showcased all over the Field Museum, and casts a long shadow over the paleoart of most of the last century. Many of his dinosaurs became the iconic representations of their taxa, arguably persisting even after the dinosaur renaissance of the last thirty to forty years radically altered our ideas of their posture, physiology, evolutionary affinities, and even behavior.

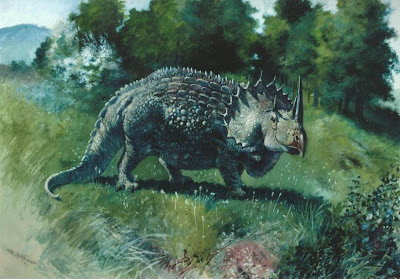

Knight, born in 1874, was working at a time that paleontology truly was a new frontier: the bitter rivalry between paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope had resulted in many fossils being pulled out of the American west, and exactly what they all meant was still being sorted out. It didn't help that Marsh and Cope's bone war produced a tangled taxonomy that's still being sorted out today. Witness Knight's Agathaumas, a piece based on a smattering of fossils named by Cope. It required him to fill in with his imagination what time did not preserve.

Knight's very reptilian Agathaumas. From wikimedia commons.

An astute commenter reminded me of the Knight Agathaumas a couple of weeks ago when I wrote about a similar version, by German artist Heinrich Harder. I had seen it before, but for some reason didn't associate it with Knight. It's not one of his truly iconic pieces, though I am oddly attracted to it. It's certainly a relic of a time when dinosaurs were believed to be much more reptilian than our modern conception of them as a truly unique branch on the tree of life. This Agathaumas has iguana-like features, and you can see an affinity to my favorite Knight piece, Leaping Laelaps.

From wikimedia commons.

Aggie could be right around the bend, really. This is my favorite dinosaur painting of all time. It's not posed; it's a snapshot of these dinosaur's lives. Laelaps is now known as Dryptosaurus, and though the anatomy here isn't up to date, it's irrelevant. This is the kind of piece that plants a seed and inspires a person to explore natural history.

Amazingly, Knight was nearly blind. Not only had he inherited astigmatism, an errant rock severely damaged his right eye when he was only six. These expansive visions of prehistoric life were created by a man who had to work with his face inches from the canvas to see what he was doing.

Trachodon, now Anatotitan. From wikimedia commons.

Knight's paintings were a doorway through which artists could explore prehistoric worlds, but I also think about the impact they had on other observers. Imagine stepping into the Field Museum or the American Museum of Natural History at a time before television existed. Knight's colossal murals would have plunged visitors into the depths of Earth's history, bringing them face to face with a cultureless world, expanding their imaginations. I wish I could rewire my brain so I could experience these paintings as purely as their original audiences did.

Knight's La Brea Tar Pits mural. From wikimedia commons.

I've recommended it before, and I'll do it again. Indiana University Press's commemorative edition of Knight's Life Through the Ages is a great addition to your bookshelf. It goes well beyond his Mesozoic reconstructions and shows just how absorbed he was by nature in general, and how vivid his imagination was when conjuring scenes lost to the ages. It's also a great read, having been published in the mid 1940's, when Knight was a science lecturer as well as artist. Some of his page-long descriptions read like he was pitching them to Walt Disney for use in Fantasia: "A gentle breeze blows softly through the forest glades; the silence is oppressive, for no song of birds, no cry of an animal breaks the stillness of that shadowed land," he writes, describing a scene from the Carboniferous. Stephen Jay Gould wrote a foreword for this edition, and as a long admirer of Knight's, it makes you wonder if some of his gaudier prose was inspired in part by Knight.

More on Knight: The official website, chock full of information and images. The Open Source Paleontologist reviewed Knight's autobiography. Check out the Field Museum's Knight collection on-line here. It would behoove you to check out William Stout's Knight sketchbooks. Browse the Vintage Dinosaur Art flickr pool to see plenty of examples of blatant Knight rip offs!