A year ago, I wrote a guest post for the Scientific American guest blog, called "How to Name a Dinosaur." Still kind of tickles me that I have my name associated with SciAm, even if it's such a minor way. So, here it is again.You had no reason to expect a good weekend as you began a long-dreaded yard project. Come Monday morning’s office discussions of sporting events and parties, you would be nursing an aching back. But with a single strike of your shovel, your yard gave you a story to top any tale of drunken debauchery recounted over cubicle partitions: waiting less than 20 inches under the sod was a fossilized femur that hadn’t seen the sun in 120 million years.

Since plausibility has already been pretty well throttled, let’s say that in the kind of radically simplified form of paleontology children’s books employ, scientists from a local museum immediately recognize the bone as belonging to a dinosaur that is brand new to science. In a savvy move thought up by the museum’s public relations office, you will be given the honor of naming the beast. It’s a heavy burden, and you recognize quickly that it’s going to require careful deliberation. You don’t want your dinosaur to be laughed off of the paleontological stage, after all.

The name a dinosaur is given is subjected to the same scrutiny as the description of its skeletal remains. It’s a minefield, and there are many ways the unwary can go astray. A shaky grasp of latin might result in incorrect pluralization or an awkward suffix. Noble dedications to local culture and language can be misspelled. Worse yet, it might just sound silly. Avoid all of these, and your name still might be brushed off because you were too conservative.

As a first step, you might narrow down your choices depending on the kind of dinosaur you're naming. No matter what kind you've got on your hands, there is likely an informal signifier in the form of a suffix to its generic name. For an ostrich-mimic, you might choose

-mimus. A herbivore with a beaked, horned, frilled skull receives a

-ceratops. For a dromaeosaur,

-raptor works nicely. To get across the tenacity of a predatory theropod,

-venator sounds really cool. A relative of

Baryonyx or

Spinosaurus might pay tribute to the crocodiles its snout resembles with

-suchus. Sauropods work well with

-titan. To play it safe, choose the truly classic dinosaurian suffix,

-saurus.

Generous fellow that I am, I’ll provide further guidance in the form of three broad categories which apply to most dinosaur names. Individual examples can bleed between them, of course. Since we’re about to turn the corner into 2011, I’ll also use the opportunity to employ some of my favorite dinosaur names of 2010 as examples. One note before I start: for brevity’s sake, I'm only giving advice for the generic half of the Linnaean binomial, in other words, the

Tyrannosaurus but not the

rex. You're on your own when deciding on a specific name. If you're stuck, name it for your mom, and you'll do alright.

Stick with TraditionThe 19th century scientists who founded the discipline of paleontology as we know it often stuck to simple anatomical descriptions of the fossilized creatures they examined. Gideon Mantell kept it basic with his

Iguanodon, “iguana tooth.” Since he only had teeth to go on, we can’t fault him for lack of imagination. 1838’s

Poekilopleuron simply means “varied ribs.” Joseph Leidy, the founder of American paleontology, chose

Hadrosaurus as the name of the world’s first mountable dinosaur skeleton. It means “bulky lizard,” which is accurate, if not terribly evocative. 2010 saw the introduction of a few anatomically-named dinosaurs, such as the abelisaur

Austrocheirus, the “southern claw.”

Pneumatoraptor, from Hungary, was named for the tiny air pockets infusing its scapulocoracoid.

Considering the classical training of the early paleontologists, many of them had a firm grasp of mythology. Edward Drinker Cope’s

Laelaps was named for a tenacious dog of Greek mythology - unfortunately, a mite had already been given the name, and it’s now the “tearing lizard,”

Dryptosaurus. One of my favorite mythologically themed dinosaur names of recent years is the brachiosaur

Abydosaurus, whose skull was found with four cervical vertebrae near the Green River at Dinosaur National Monument. Its name refers to the town of Abydos in ancient Egypt, where the god Osiris’ own head and neck were buried in the Nile. Instead of providing insight into the anatomy of the great beast it was given to, the name tells a story about its discovery millions of years after it walked.

A third subset of traditional names is to pay tribute to another researcher, fossil hunter, or someone else who was instrumental in the discovery of the dinosaur or the field in general. This is normally done in the specific name, but entire genera are occasionally dedicated to one person, as in the ornithischians

Othnelia and

Drinker, honoring the prolific rivals of the

Bone Wars. Just this month, a North American troodontid named

Geminiraptor saurezorum was announced, and both halves of the binomial are dedicated to a pair of scientist sisters named Suarez. If you’re familiar with matters astrological, you might correctly guess that they’re twins.

Go NativeIf you want to be cutting edge, jump on to the growing trend of paying tribute to local places, culture, and history. It’s a heartening trend, as paleontologists often rely on locals for support of their work, and it counteracts the old stereotype of paleontologists ripping fossils from the ground for the enrichment of far-off institutions. And it engages cultures in ways that sticking stubbornly to Latin and Greek can’t. While the names of new dinosaurs coming out of China may confound the tongue of someone from Helsinki, Buenos Aires, or Des Moines, Chinese kids probably appreciate having dinosaurs of their own, such as

Mei long, the “sleeping dragon.” On the other hand, local tributes can result in clunkers like this year’s dynamic duo

Koreanosaurus or

Koreaceratops, which recieved a fair amount of

web snark.

This year has seen plenty of good newcomers in this category, though. A few of them paid tribute to the cultures who first inhabited the American West. Two of these derive from the Navajo language.

Seitaad is named for a mythological beast that swallowed its prey in sand dunes, which also alludes to the manner of the small sauropodomorph's death.

Bistahieversor’s name is derived from a Navajo description of local geography. The Zuni people have their own dinosaur as well, a duckbill named

Jeyawati, which means “grinding tooth” in their language.

One of the most inspired members of this class of dinosaur names comes from Romania. When I first read about it, it sounded like some beast out of Tolkein’s Middle-Earth. But the island-dwelling theropod

Balaur bondoc refers to actual mythology with a decidedly local flavor. It’s standard for descriptions of dinosaurs to include sections on the etymology of their names, but

Balaur’s is exceptional, exploring the twisting roots of the word’s various meanings that approach the evolutionary tree of life for richness and complexity. Lead author Zoltan Csiki writes that

Balaur’s name is “motivated both by the classical association between dinosaurs (especially theropods) and dragon-like creatures, as well as by the fact that balaur is a mythological creature with links to both reptiles (snakes) and birds (wings)...” Who knew that reading the description of a dinosaur could also be a lesson in Romanian mythology?

Make a SplashIt’s part of a paleontologist’s job to focus on the deep past, but some also think forward to the public impact of their discoveries. Lately, University of Chicago’s Paul Sereno has seemed especially focused on the public-relations side of paleontology; in 2009, he unveiled the controversial

Raptorex, which might be mistaken for the name of a Pokemon character, as well as

a slew of Mesozoic crocodilians with nicknames like BoarCroc, DogCroc, RatCroc, and the unfortunate PancakeCroc.

This year, even a mild-mannered iguanodont received an impactful name in

Iguanacolossus. But 2010 will truly be remembered as the

Year of Ceratopsians, and some of the catchiest new names come from the beak-and-horns set, including

Medusaceratops,

Kosmoceratops, and

Mojoceratops.

One of my favorite dinosaur names of this year or any other is

Diabloceratops, which describes the fierce twin horns protruding from the back of its frill and is just plain fun to say. If he was writing

Jurassic Park today, I imagine that Michael Crichton would be strongly tempted to include a

Diabloceratops paddock on the island.

A Final Word of AdviceGo bold. Shoot for a word that will make some emotional impact. A dinosaur’s name is often the first impression it will present to the public. Though the standard pantheon of the most popular dinosaurs - you know, the ones even my grandmother can name - has been in place for a century, it’s always susceptible to invasion by a charismatic newcomer, as was proven by

Velociraptor’s leap into the public consciousness in the 1990’s. If a novelist, comic artist, or screenwriter latches onto the name of your dinosaur, it could very well be fast-tracked for celebrity.

Above all, remember that the name you choose for your backyard discovery will say as much about you as it does about the bones in the museum.

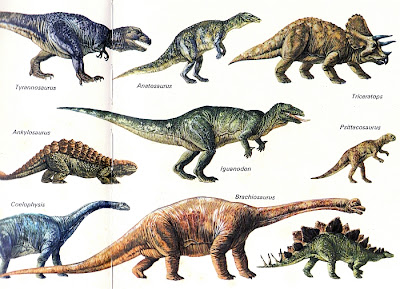

Illustration copyright

Matt Van Rooijen, used with his permission.