Another entry in the Dinosaur Dynasty book series from 1993, The Real Monsters focuses on a select few dinosaurs that embody the largest, and often toothiest, that said archosaurian lineage had to offer at various points in the Mesozoic. As such, a scary-looking tyrannosaur with yellowing teeth and a tiny, beady eye leers out from the cover, for maximum child-enticing appeal. For as every kid knows, the coolest dinosaurs are those that look like they would happily chew, slice, gore, stamp, or otherwise pulverise you to death without so much as blinking a nictitating membrane. This is a book dedicated to them.

Showing posts with label Dougal Dixon. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Dougal Dixon. Show all posts

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

Tuesday, November 12, 2013

Vintage Dinosaur Art: Dinosaurs - Giants of the Earth

Published as part of the five-book Dinosaur Dynasty series back in 1993, Giants of the Earth was my childhood introduction to pop-palaeo stalwart Dougal Dixon. Each book in the series dealt with a different aspect of dinosaur science, with this one looking at, as the cover implies, their evolutionary history. The artwork is of a surprisingly high standard for the time, even if the obligatory early '90s Sibbick rip-offs are present and correct. The cover art, by Steve Kirk, is exemplary - a couple of very small tweaks, and it would pass muster even today. And the colour scheme is quite lovely. You can't go far wrong with stripy Styracosaurus horns.

Wednesday, September 18, 2013

Vintage Dinosaur Art: Be a Dinosaur Detective

There's been so much Dougal Dixon on this blog in the last few years, I've actually petitioned David to rename the it to 'Love in the Time of Dougal'. He refused, but nevertheless, the rather prolific author surely featured significantly in the childhoods of many readers. Certainly he featured in Adam Smith's, the present-day plesiosaur and dinosaur biscuit expert, for the Dougal-authored Be a Dinosaur Detective is another book lent to me by him.

Of course, while it's important to take a moment to honour Dixie Doug (as his little known country-and-western alter ego* is named), we're really here for the artwork; it's Vintage Dinosaur Art, after all, not The Fantabulous 1980s World of Dougal Dixon (although that sounds like it has potential, you know). Steve Lings was on illustration duty for BaDD, although the cover looks like it might have been painted by a different artist. Bernard Robinson aficionados will note that the sauropod's body is copied from his painting of Apatosaurus (described by Darren Naish as "very rotund"), but the artist has improved upon it with a helter skelter neck and slightly amused facial expression. The children depicted in the bubble serve to represent the reader(s) for size comparison purposes inside the book, which is fortunate in that we never have to look that closely at their freakish faces again.

Brrrr.

Dating from 1987, many of the dinosaurs in this book are quite 'modern' in appearance; this T. rex, for example, has huge (if slightly odd-looking) muscles and birdlike feet complete with tarsal scutes. The tail might be on the ground, but the posture's definitely leaning more towards the horizontal.

Other theropods fare similarly; Deinonychus, Dromiceiomimus (or is it Ornithomimus?) and Compsognathus, while conspicuously scaly (or is that warty?) by modern standards, are nevertheless depicted running at full pelt. Being tiny, the Compsognathus is being threatened with an enormous magnifying glass, presumably to reduce it to a charred husk that can be ground up and sold in buckets with a side order of fries and a Diet Coke, please. Lings' Baryonyx is low slung, but not quite a quadruped, as it was frequently depicted in the late '80s. He also manages to avoid falling into the trap of giving it a freakish hand, with one giant hook surrounded by a cluster of tiny vestigial digits, as others did back in the day.

By way of contrast with the theropods, the sauropod spread is decidedly retro, with a miserable bunch of bland-looking, tail-dragging schlubs. At least Opistho...Opisthocoeli...this one livens things up by rearing and adopting a face that's all, "Look ma! No hands!"

BaDD invents non-technical names for each key dinosaur group, the better that kids can remember them. This way, ankylosaurs become the 'welded dinosaurs' ('cos they're fused, see?), while ornithopods become the, er, 'two-footed plant-eaters'. The Iguanodon appears to take after a John Sibbick piece, but we all know what you're looking at, you dirty scoundrel. As if having a tacky gag stuck to its head wasn't enough, Tsintaosaurus just had to go and look so damn sad about it. It's like it's anticipating your reaction. Poor Tsintaosaurus; the resonating chambers are hypothetical, and there's no reason that they always have to be inflated in that way, and yet people keep on making it a literal dick head (see also: this toy).

Since I've been told off about this before, I feel obliged to point out that BaDD features a decent overview of dinosaurs' skeletal features and possible lifestyles, and - since the book is all about sleuthing - posits questions on why animals may have evolved certain features. Note the question on 'duck-bill' hands - the answer is quite revealing of how dinosaur books in the time had one foot in the pre-Dino Renaissance past:

Lings is a good artist, but his approach to ceratopsians is a little odd, and may be informed by the work of John McLoughlin, who believed (as recently discussed) that the animals' frills would have been anchored to their backs by ludicrous amounts of muscle, rendering them spiny-shouldered neckless wonders. Hence the flat-headed Styracosaurus we see here, and a similar Triceratops elsewhere.

Of course, it's not all dinosaurs in BaDD - those pesky 'other' Mesozoic animals make their contractually-obliged appearances, too. The plesiosaurs are pretty good, all things considered, boasting retracted nostrils, eyes in the right sort of place (ish) and even vertical tail fins. This might also be the cheeriest Kronosaurus ever committed to paper. Why, he's even encouraging kids to have a go at making their own plesiosaur out of plasticine and string. However, the book doesn't mention that you will also require a palaeontologist on hand to give you a slap on the wrist whenever you start snaking the neck around. There's no arguing with biomechanics.

Pterosaurs pop up too, with the obligatory Burianesque Pteranodon joined by an alarmingly purple Quetzalcoatlus. We're out of Pin Headed Nightmare Monster territory by this time, but the azdharchid still looks a little strange, what with its stick-thin arms and capsule-shaped body.

There's also the fact that the Pteranodon are apparently clinging to a sheer rock face upside-down, but that's cool. Careful analysis of highly compressed JPEG photographs of Pteranodon fossils has revealed that they possessed gecko-like pads on their hands and feet. It's not mentioned in Mark Witton's book 'cos he doesn't know nothing about pterosaurs, that guy.

As is par for the course in a 1980s book, Archaeopteryx is featured alongside the pterosaurs as a 'Mesozoic flying animal', although it is nevertheless noted that birds are thought to have evolved from dinosaurs. This is a classic 'wings...but with hands!' rendition of the animal, although you've got to love that colour scheme. Wild.

It's quiz time! Yes, there is a little irony in including an '80s-tastic Spinosaurus in a lineup like this, given that a great deal of its anatomy has, indeed, been completely made up (albeit by scientists making educated guesses, rather than Ray Harryhausen - see below). The ineffectual four-fingered hands and grinning 'carnosaur' fizzog are just fantastic. It seems to be waving hello. I wouldn't be taken in.

And finally...the two imposters in the quiz. On the left we have a gliding ankylosaur with theropod hands, a concept so gloriously silly that Hasbro even made a 'genetic mutation' toy out of it (oh yes they did). On the right we have the titular creature from The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, which is a beautiful thing to crowbar into a 1980s children's dinosaur book. His characteristically cheerful expression makes me wonder if someone's made a toy out of him - preferably, a plush toy. If not, someone needs to work on it, post haste. Go on, Internet, don't let me down.

*This is a complete lie.

Of course, while it's important to take a moment to honour Dixie Doug (as his little known country-and-western alter ego* is named), we're really here for the artwork; it's Vintage Dinosaur Art, after all, not The Fantabulous 1980s World of Dougal Dixon (although that sounds like it has potential, you know). Steve Lings was on illustration duty for BaDD, although the cover looks like it might have been painted by a different artist. Bernard Robinson aficionados will note that the sauropod's body is copied from his painting of Apatosaurus (described by Darren Naish as "very rotund"), but the artist has improved upon it with a helter skelter neck and slightly amused facial expression. The children depicted in the bubble serve to represent the reader(s) for size comparison purposes inside the book, which is fortunate in that we never have to look that closely at their freakish faces again.

Brrrr.

Dating from 1987, many of the dinosaurs in this book are quite 'modern' in appearance; this T. rex, for example, has huge (if slightly odd-looking) muscles and birdlike feet complete with tarsal scutes. The tail might be on the ground, but the posture's definitely leaning more towards the horizontal.

Other theropods fare similarly; Deinonychus, Dromiceiomimus (or is it Ornithomimus?) and Compsognathus, while conspicuously scaly (or is that warty?) by modern standards, are nevertheless depicted running at full pelt. Being tiny, the Compsognathus is being threatened with an enormous magnifying glass, presumably to reduce it to a charred husk that can be ground up and sold in buckets with a side order of fries and a Diet Coke, please. Lings' Baryonyx is low slung, but not quite a quadruped, as it was frequently depicted in the late '80s. He also manages to avoid falling into the trap of giving it a freakish hand, with one giant hook surrounded by a cluster of tiny vestigial digits, as others did back in the day.

By way of contrast with the theropods, the sauropod spread is decidedly retro, with a miserable bunch of bland-looking, tail-dragging schlubs. At least Opistho...Opisthocoeli...this one livens things up by rearing and adopting a face that's all, "Look ma! No hands!"

BaDD invents non-technical names for each key dinosaur group, the better that kids can remember them. This way, ankylosaurs become the 'welded dinosaurs' ('cos they're fused, see?), while ornithopods become the, er, 'two-footed plant-eaters'. The Iguanodon appears to take after a John Sibbick piece, but we all know what you're looking at, you dirty scoundrel. As if having a tacky gag stuck to its head wasn't enough, Tsintaosaurus just had to go and look so damn sad about it. It's like it's anticipating your reaction. Poor Tsintaosaurus; the resonating chambers are hypothetical, and there's no reason that they always have to be inflated in that way, and yet people keep on making it a literal dick head (see also: this toy).

Since I've been told off about this before, I feel obliged to point out that BaDD features a decent overview of dinosaurs' skeletal features and possible lifestyles, and - since the book is all about sleuthing - posits questions on why animals may have evolved certain features. Note the question on 'duck-bill' hands - the answer is quite revealing of how dinosaur books in the time had one foot in the pre-Dino Renaissance past:

"A duck-bill's paddle-like hands would have helped it to swim."Wouldn't it have helped to not have the hand be so narrow? Oh, whatever.

Lings is a good artist, but his approach to ceratopsians is a little odd, and may be informed by the work of John McLoughlin, who believed (as recently discussed) that the animals' frills would have been anchored to their backs by ludicrous amounts of muscle, rendering them spiny-shouldered neckless wonders. Hence the flat-headed Styracosaurus we see here, and a similar Triceratops elsewhere.

Of course, it's not all dinosaurs in BaDD - those pesky 'other' Mesozoic animals make their contractually-obliged appearances, too. The plesiosaurs are pretty good, all things considered, boasting retracted nostrils, eyes in the right sort of place (ish) and even vertical tail fins. This might also be the cheeriest Kronosaurus ever committed to paper. Why, he's even encouraging kids to have a go at making their own plesiosaur out of plasticine and string. However, the book doesn't mention that you will also require a palaeontologist on hand to give you a slap on the wrist whenever you start snaking the neck around. There's no arguing with biomechanics.

Pterosaurs pop up too, with the obligatory Burianesque Pteranodon joined by an alarmingly purple Quetzalcoatlus. We're out of Pin Headed Nightmare Monster territory by this time, but the azdharchid still looks a little strange, what with its stick-thin arms and capsule-shaped body.

There's also the fact that the Pteranodon are apparently clinging to a sheer rock face upside-down, but that's cool. Careful analysis of highly compressed JPEG photographs of Pteranodon fossils has revealed that they possessed gecko-like pads on their hands and feet. It's not mentioned in Mark Witton's book 'cos he doesn't know nothing about pterosaurs, that guy.

As is par for the course in a 1980s book, Archaeopteryx is featured alongside the pterosaurs as a 'Mesozoic flying animal', although it is nevertheless noted that birds are thought to have evolved from dinosaurs. This is a classic 'wings...but with hands!' rendition of the animal, although you've got to love that colour scheme. Wild.

It's quiz time! Yes, there is a little irony in including an '80s-tastic Spinosaurus in a lineup like this, given that a great deal of its anatomy has, indeed, been completely made up (albeit by scientists making educated guesses, rather than Ray Harryhausen - see below). The ineffectual four-fingered hands and grinning 'carnosaur' fizzog are just fantastic. It seems to be waving hello. I wouldn't be taken in.

And finally...the two imposters in the quiz. On the left we have a gliding ankylosaur with theropod hands, a concept so gloriously silly that Hasbro even made a 'genetic mutation' toy out of it (oh yes they did). On the right we have the titular creature from The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, which is a beautiful thing to crowbar into a 1980s children's dinosaur book. His characteristically cheerful expression makes me wonder if someone's made a toy out of him - preferably, a plush toy. If not, someone needs to work on it, post haste. Go on, Internet, don't let me down.

*This is a complete lie.

Labels:

Dougal Dixon,

Steve Lings,

vintage dinosaur art

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

Vintage Dinosaur Art: one last look at The Age of Dinosaurs: A Photographic Record

A final airing for Jane Burton's glorious photographs, with a little 1980s nuttiness along the way! In case you've missed them, check out part 1 and part 2, too.

While this book is really all about the photography (of course), there are a small number of illustrations in the opening chapter which, to be honest, aren't really much to write home about. However, at least one is amusing in that it appears to be a lesson in the science of reconstructing extinct animals, as intended for pre-Dino Renaissance palaeoartists.

For crying out loud, the skeletal reconstruction won't fit inside the life restoration, never mind the muscular reconstruction. What was the artist (Alan Male, if you were wondering) thinking? At least the hadrosaur is waving hello, albeit while delivering a rather withering look from its not-entirely-in-proportion face.

Back to the photography...we're safe there. In spite of the book's title, a lot of the best photographs actually feature Palaeozoic animals, going back as far as the Carboniferous (yes, the title of this blog series is revealed to be a swizz once again). This study of the minor celebrity and Permian synapsid Dimetrodon is very lovely; a moody depiction of the ever-popular creature rising at dawn, complete with a layer of fog to add that desired element of primordial mystery. The composition and lighting are excellent, and really draw attention to the animal's most famous feature.

Although it's somewhat less convincing overall (the waves in the background photograph make the animals look like the miniatures that they are), the models in this shot of Tanystropheus and Nothosaurus are still wonderful. The eye is drawn immediately to the two sparring nothosaurs in the centre of the scene, flashing their teeth at one another; once again, it creates a sense of the everyday drama of these animals' lives without resorting to over-the-top action and/or motion blur. The careful way that the models have been arranged helps enhance the feel that this is a casual snapshot of real creatures - it's just a shame about the backdrop...

While the main subject of the image below is the therapsid Lycaenops (depicted with very fetching stripy green skin), it's hard to avoid being drawn to the hulking brown brute behind it - what could it be? In fact, it's a rather odd-looking reconstruction of Pareiasaurus, which was closely related to the more popularly known Scutosaurus, and would have looked pretty similar. Still, I love the way that the fanged carnivore is made to look a pipsqueak by the bulky herbivore - it's good to see a pareiasaur standing its ground. Dougal Dixon would like to remind us, however, that

This scene, depicting a Cynognathus family group, is effective for similar reasons to the Dimetrodon picture - it's superbly and evocatively lit (but hasn't scanned well, for which I can only apologise), and while portraying the animals in near-silhouette may seem like a bit of a cop-out, closer inspection reveals that a lot of fine details have been put into the models. The poses are very well observed, too, particularly the juvenile raising its head as if begging for food from its mother.

Dougal Dixon posits that Lystrosaurus, the dicynodont famous for enjoying a global hegemony in the Early Triassic that would make Rupert Murdoch furious with envy, lived an amphibious lifestyle like a modern hippopotamus. Exactly how well-supported this idea is these days I'm not sure, but I have the feeling the answer is 'not very' (readers should feel free to enlighten me!). Regardless, the photo is quite well done, if a little uninteresting. You know, someone really ought to animate its stumpy limbs paddling along, and then we can all stare at it a while listening to a suitable musical accompaniment.

FINALLY...one of the best photos in the book. The Longisquama model is a marvel - packed with extremely fine detail, gloriously painted and shot in pin-sharp focus. These days, Longisquama is best known as the prime candidate for the ancestor of birds, something that Dougal Dixon very presciently mentions:

And with that cheap shot out of the way, I'm all done! Don't worry - the recycling of books ends here, as I'm being loaned some all new tomes via the magic of the mail by a very kind reader. Stick around! Pretty please.

While this book is really all about the photography (of course), there are a small number of illustrations in the opening chapter which, to be honest, aren't really much to write home about. However, at least one is amusing in that it appears to be a lesson in the science of reconstructing extinct animals, as intended for pre-Dino Renaissance palaeoartists.

- Start with a thorough, modern skeletal reconstruction.

- Carefully apply musculature, based on knowledge of the skeleton and comparisons with living animals.

- Ignore all that shit and just draw something that basically resembles what you think the animal in question should look like. Dinosaurs were pathetic evolutionary dead-ends, so be sure to give them spindly limbs incapable of carrying their comically ponderous bulk.

Back to the photography...we're safe there. In spite of the book's title, a lot of the best photographs actually feature Palaeozoic animals, going back as far as the Carboniferous (yes, the title of this blog series is revealed to be a swizz once again). This study of the minor celebrity and Permian synapsid Dimetrodon is very lovely; a moody depiction of the ever-popular creature rising at dawn, complete with a layer of fog to add that desired element of primordial mystery. The composition and lighting are excellent, and really draw attention to the animal's most famous feature.

"[Lycaenops] has nothing to fear from the great plant-eater which it could easily kill if it were hungry."Yeah, whatever, Dougal.

"It is thought that these specialised scales [on its back] represent an early stage in the evolution of feathers, and so this line of animals could possibly have developed into birds."Genius. Of course, you do have to ignore all the evidence supporting a dinosaurian origin for the birds, including skeletal, integumentary and even behavioural links in sufficient stacks of specimens to fill the warehouse from Raiders of the Lost Ark. But that's easily done with a bit of harumphing and moving of goalposts, so that's OK.

Labels:

Dougal Dixon,

Jane Burton,

vintage dinosaur art

Friday, October 19, 2012

Vintage Dinosaur Art: The Illustrated Dinosaur Encyclopedia - Part 2.2

Yesterday, I mentioned that the sauropods in this book aren't especially good, drawing particular attention to the somewhat half-finished looking Saltasaurus. Actually, they're quite typical of the time - rather anachronistic, unwieldy, bloated, irrelevant and ugly, not unlike the British Royal Family. While other dinosaurs were receiving a facelift, sauropods tended to get left behind a little - although they were hauled out of the swamps, they still tended to drag their tails around everywhere like outsized thunder lizards. The artistic execution remains pretty good here, though, and I am particularly fond of the glassy, cold black eyes. Like a doll's eyes.

Of course, there's also that brachiosaur in the background which appears to be, well, tiny, due to an unfortunate perspective quirk caused by the ferns in the background. I dunno, maybe it's a baby.

Meanwhile, this Diplodocus looks rather like the Invicta toy, which in turn strongly resembles palaeoart by Burian, among others. Fortunately, that also means it is possessed of a more convincingly organic, fluid quality than the brachiosaur, and is definitely one of the better sauropods in the book (even if they still insist on the tail-dragging). I'm also fond of the rearing individual in the background (although I have the feeling that it's been cribbed from somewhere) - if nothing else, it instantly livens up the composition of the scene.

Euoplocephalus, being cool. I like this one - the pose provides a decent overview of the animal, but the twisty head and braced forelimbs add a little interest and liveliness beyond that of a boring Diagnostic Lateral View (DLV). It's also very nicely and evocatively lit in a way that hints at the animal's sheer bulk and presence, even if the hips haven't been made wide enough. Unfortunately, someone placed a rather distracting little detail in the background.

Many artists have attempted to illustrate an ankylosaur smacking a tyrannosaur with its tail club, and virtually none of them have done it well. This is no exception to the rule, with both parties looking rather limp and inert; this is especially true of the tyrannosaur, whose arms seem to have been broken in a number of places (presumably through the SHEER FORCE OF THE IMPACT).

This has to be one of the more unusual 'post-tripod' illustrations of Iguanodon that I've ever seen. Even when taking the perspective into consideration, that is one seriously pin-headed beastie. To make matters worse, this massive, pillar-limbed creature is supposed to be "Iguanodon mantelli" (aka Dollodon seelyi, or possibly Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis), which was actually a rather slender and short-armed creature, much smaller than the more famous Iguanodon bernissartensis. Having said all that, I once again have the feeling that this is a rip-off of a piece by a more established palaeoartist, but can't quite put my finger on which one. As they might say in The Beano, "Help me, readers!"

And finally: you've got to wonder what they're looking at. Maybe an anachronistic mutant Tyrannosaurus has come tramping over the hill nearby a la the Rite of Spring segment in Fantasia. The keen-eyed will spot the Sibbick riffs here - in fact, the theropod looks rather like his 1980s Dilophosaurus with the crests removed.

That's all for now! If I've missed any of your favourites, then please do alert me in the comments and I'll compile a farewell post containing them all...

Thursday, October 18, 2012

Vintage Dinosaur Art: The Illustrated Dinosaur Encyclopedia - Part 2.1

In a break with convention, I'm splitting this week's post into two parts. Any complaints? No? Good.

You'll recall 1988's The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs from a couple of weeks back. Like several thousand other dinosaur books in the 1980s it was written, although not illustrated, by good ol' Dougal Dixon, or 'Dixie Doug' as he wasn't known. Illustration duties went to Andrew Robinson and David Johnston, but unfortunately the individual pieces aren't credited.

The book comes across as something of a second-rate version of the Norman/Sibbick encyclopedia from earlier in that most beloved of decades, which I covered slavishly a short while ago. Many of the illustrations look remarkably similar to Sibbick's, although it can be difficult to tell when they weren't simply based on the same skeletal mounts or palaeoart memes.

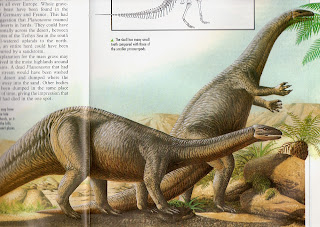

These Plateosaurus certainly look very familiar, but then it was popular among many artists to show the animal as both an upright biped and impossi-quadruped - all the better to demonstrate the animal's supposed range of motion. Whatever the case, while these obviously can't match up to the artistic flair of a Sibbick, they're nice enough - if a little wrinkly. Actually, they remind me of nothing so much as mid-range dinosaur toys from the early '90s, which often looked like oddly pointy prunes.

The artist was clearly aiming for a similar effect with this Panoplosaurus (or is it Edmontonia?), but unfortunately fell a little short, mostly thanks to that rather awkward right forepaw. Everyone do the Nodosaur Shuffle! Still, this is a nicely painted scene, with lovely, crisp detailing on the ankylosaur and parched riverbed.

You'll recall 1988's The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs from a couple of weeks back. Like several thousand other dinosaur books in the 1980s it was written, although not illustrated, by good ol' Dougal Dixon, or 'Dixie Doug' as he wasn't known. Illustration duties went to Andrew Robinson and David Johnston, but unfortunately the individual pieces aren't credited.

The book comes across as something of a second-rate version of the Norman/Sibbick encyclopedia from earlier in that most beloved of decades, which I covered slavishly a short while ago. Many of the illustrations look remarkably similar to Sibbick's, although it can be difficult to tell when they weren't simply based on the same skeletal mounts or palaeoart memes.

Speaking of pointy things, this Styracosaurus marks a welcome departure from the majority of the illustrations in the book in that it's not depicted in lateral view, heading right. Always a spectacular-looking animal when seen head-on, the creature's menacing, confrontational aspect is only enhanced by the artist's penchant for sinister red eyes. That, and it's clearly heading towards the viewer with some speed, kicking up a cloud of dust that's worthy of Sibbick himself (who was always a fan of bilious gritty stuff).

This Saltasaurus is an odd one - unlike most of the other illustrations in the book (including the Panoplosaurus) it's rather muddy and sloppy-looking, even if the dinosaur is bedecked in yet another pattern seemingly evolved to send attacking theropods wandering drunkenly away in a cross-eyed stupor. The left manus also seems to have been borrowed from a different animal, and looks a bit like the rear scoop on a JCB. Sauropods don't tend to do too well in this book...but more on that tomorrow.

Ah, that's better! Much more careful detailing on this Stegoceras, a livery the right side of '1970s curtains' on the lairy-o-meter and, superbly, a pair of individuals going 'head to head' (ahem) in the back. But wait, what's this?

...

Well now...I'm quite lost for words. Was the expression of intense pain really necessary? I mean, you don't see zebras collapse in the middle of the Serengeti, their faces contorted into grotesque grimaces of equine agony, now do you? I blame Dougal Dixon for this. I bet he sneaked into the artist's studio in the dead of night, dressed in an oversized trenchcoat and wide-brimmed hat, cigarette dangling from his mouth and muttered through clenched teeth "I'll tells ya what the kids gotta see, son. Dixie Doug's gonna teach them a little life lesson right here in his blessed dinosaur book."

More tomorrow!

Well now...I'm quite lost for words. Was the expression of intense pain really necessary? I mean, you don't see zebras collapse in the middle of the Serengeti, their faces contorted into grotesque grimaces of equine agony, now do you? I blame Dougal Dixon for this. I bet he sneaked into the artist's studio in the dead of night, dressed in an oversized trenchcoat and wide-brimmed hat, cigarette dangling from his mouth and muttered through clenched teeth "I'll tells ya what the kids gotta see, son. Dixie Doug's gonna teach them a little life lesson right here in his blessed dinosaur book."

More tomorrow!

Tuesday, October 9, 2012

Vintage Dinosaur Art: more from The Age of Dinosaurs: A Photographic Record

It's time for another trip into the world of lovingly detailed miniature dinosaurs, as photographed by Jane Burton (with commentary from Dougal Dixon, because it was the 1980s). For those who missed the first part, FOR SHAME! Go back and check that out first - it's worth it for the Saltopus alone. In addition, I don't want to have to introduce the book again. I've got a stinking cold, you know, and am here as long as the mug of Lemsip lasts.

Anyway, without further delay, here's a slightly psychedelic hadrosaur!

While I appreciate a sudden explosion of pink blooms in a book otherwise filled with rather earthy tones as much as the next person, there's something quite uncanny about that eye.This picture is also rather jarring in that there aren't really any other close-ups like this in this book - this flower power Lambeosaurus profile shot seems a bit out of place.

Ah, that's more like it. As with the best shots in this book, there is an effective illusion of scale here, while the two Pachycephalosaurus models are wonderfully detailed and superbly posed, flashing their bright blue heads at one another. By far the best shots in this book are those that avoid any gimmicks and remain sharp and in focus, but this can also result in scenes that are rather static and dull. Having two animals displaying is an effective way to circumvent that problem, as it adds drama to the scene. This is further bolstered by the text, which describes this encounter as the warm up to a full-on headbutting session.

Where there is an attempt at gimmickry - as in the motion blur around these Struthiomimus - things can start to fall apart. Here, the blur is so extreme that it makes the animals look as if they have been fired out of a cannon; it doesn't help that the individual in the foreground appears to be flying over the water. Yeah, we get it, they were fast.

As I mentioned last week, there are only a couple of attempts at sauropods, and it's easy to imagine why - making tiny models of such huge animals look convincing in a photograph must be very tricky indeed. This Apatosaurus pic is a pretty decent attempt, and certainly a good job is made of forcing the viewer's perspective to create an illusion of depth. It's also rather pleasing to see that the dinosaurs are up and active, with elevated tails, although admittedly this was becoming more commonplace by 1984.

Here we have some egret(-like bird)s, and...an ankylosaur. But which one? It looks rather similar to Edmontonia, but - just to remind the reader that this book has plenty of throwbacks to the Palaeontology Dark Ages - it's labelled Palaeoscincus. Palaeoscincus, like the better known Trachodon, is a very dubious genus based on teeth that nevertheless popped up a lot in dinosaur books, and most specimens assigned to it have since been reclassified. Taxonomic issues aside, though, this is definitely one of the better photos - the model plants and the interaction between the dinosaurs give it a pleasingly naturalistic feel, and the lighting is superb.

Thecodontosaurus now, and another lovely scene. Perhaps the background doesn't quite fit in terms of perspective, but the composition is effective at simultaneously showing off the animals and, through the use of vegetation, drawing the viewer into the scene. I'm not sure you'd get away with a quadrupedal Thecodontosaurus these days, but this remains a beautiful depiction of a dinosaur that doesn't get an awful lot of attention in art.

Pterosaurs are often pretty nightmarish when they're done right, but tend to be much, much worse when people get them wrong. This depiction of Quetzalcoatlus is certainly an improvement on many of those that came before it (which often had tiny, teeth-filled heads), but is still pretty bizarre. It seems to be rather lacking in musculature, and its neck looks like it's been glued on to its body; that head is still a bit too small by comparison. Rather typically for the time, the animals are portrayed skulking around a huge slab of prime rib. Brrr.

I need to go and lie down with an ice pack on my head and a thermometer wedged in my mouth, feeling sorry for myself, but here's another of my absolute favourites to finish things off for now. The model might be outdated (it's Pterodactylus), but the execution of the photo is superb - the lighting in particular is excellent, and this really does just look like very fortuitous nature photography. Gorgeous stuff.

Anyway, without further delay, here's a slightly psychedelic hadrosaur!

Labels:

Dougal Dixon,

Jane Burton,

vintage dinosaur art

Tuesday, October 2, 2012

Vintage Dinosaur Art: The Illustrated Dinosaur Encyclopedia

Dougal Dixon must be one of the all-time most prolific authors of popular dinosaur books. Back in the '80s and '90s, it certainly seemed like he was everywhere - bookshops would dedicate entire shelving units to him, and he employed a cadre of bodyguards in order to move around the streets without being mobbed by dinosaur-loving schoolchildren. (No, not really.) I've already reviewed a number of books from the DD stable, from the rather good to the plain embarrassing (hey, if you churn out that many books, there's bound to be the odd stinker every so often). This is one of the better, not to mention more weighty, entries in the Dixon oeuvre, and features a considerable number of illustrations - not by Dixon, mind you, but Andrew Robinson and David Johnston, who apparently "collaborated on many scientific and natural history publications". Most of them are pleasing enough for the late 1980s without being anything particularly special, but still offer an interesting slice of dinosaur illustration history.

Baryonyx was still the hot new kid on the block back then, and so naturally it gets the cover star treatment - depicted hurling a fish up into the air in a composition that's certainly striking and makes an excellent first impression. Unfortunately, most of the illustrations in this book follow the old-fashioned 'just-about-anatomically-rigorous-enough-to-not-look-terrible-lateral-view' model, as exemplified by Ceratosaurus below. The larger dinosaurs in particular don't get to do very much in this book, other than walk around a bit and look menacing.

Although we are never told who produced which plate, the differing styles of the illustrators quickly become apparent, although they aren't so jarring as to interrupt the book's sense of continuity (the animals are arranged in chronological order...most of the time). The artist behind, among others, the Megalosaurus below is definitely my favourite - the scaly skin textures are wonderful and their animals are much more convincing in terms of overall anatomy. Having said that, the Megalosaurus definitely owes something to the Invicta toy from the 1970s - in fact, it almost resembles someone's updated interpretation of it. "Megalosaurus was a hunter of Iguanodon," Dixon notes. Ah, that old trope...

Speaking of old tropes, here's yet another bloody T. rex that has had an ear inserted into the temporal fenestra behind its eye. WHY? Why did they keep doing this back in the '70s and '80s, and why only to T. rex? The mind boggles. Anyway, apart from that (and the dodgy skull in general) I'm actually quite fond of this one; the textures and lighting are nice, and I like that it's delivering a withering stare while standing in a pile of someone's guts. In case you were wondering, Dougal Dixon had revised his views on Tyrannosaurus by this time, noting that "scientists have reached a compromise: it was both a fast hunter and a scavenger". Hurrah!

There's nothing quite like a 1980s-style Spinosaurus - every bit as sweetly nostalgic to me as wrong-headed 'brontosaurs' (which were pretty much extinct by the time my childhood rolled around) are to slightly more well-worn older ladies and gents. Although far from the finest exemplar of the genre, the artist wins plaudits for the hilariously flattened individuals sunning themselves in the background.

More Baryonyx, and again the European spinosaur is treated to one of the book's lovelier illustrations. It's just unfortunate that the animal is only depicted in a quadrupedal stance, or this work might have aged a lot better. There's some iffy perspective work going on (that leg...hmmm), but the artist creates a lovely, painterly lakeside scene, not to mention wickedly glinting and pointy claws on the animals. The background Baryonyx has, of course, just used telekinesis to launch its fishy prey skywards with a summoning finger. After all, as Dixon points out, "Baryonyx breaks all the rules for flesh-eating dinosaurs!". Quite fitting for the '80s, really - it's totally radical, dude!

Perhaps my favourite illustration in this book, simply because it's quite 'radical' itself, is a tiny little thing positioned in the shadow of a huge scaly Deinonychus (that's clearly, uh, inspired by a considerably earlier Bakker piece). Look - feathers! At last, the wild ideas of Bakker, Paul and the rest were filtering down to a truly mainstream audience. If only you knew, 1980s Dougal Dixon, if only you knew!

Finally, a truly evil, crazily patterned Compsognathus adopts a casual air by leaning against a plant while contemplating how to cruelly finish off its insect prey. Yes.

You might have noticed that I've only scanned pictures of theropods for this post, but that's because this book is really rather thick - and I fully intend on revisiting it down the line. After all, how could I not include Plateosaurus? Everyone loves Plateosaurus...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)