Robinson was especially adept at scaly skin textures, so it's a little strange that his apatosaur is so damn wrinkly. Nevertheless, he remains consistently good at lifelike shading and lovely landscapes. His work evokes what is, for many, a nostalgic vision of tail-dragging, cold-blooded behemoths. Of course, there's something a little strange going on in this picture, as an extremely perky Barosaurus is striding into the midground. Darren Naish has already provided an excellent commentary on this image, so over to him:

"It’s as if the Barosaurus is an inter-dimensional tourist, just in from a parallel '1960s Bakkerian' universe and now strangely juxtaposed against the flabby, massively over-weight swamp-dwelling behemoths of the Zallinger era (hey, great idea for a comic)."You know, that really is a great idea for a comic - a 'when worlds collide' scenario where classic palaeoart reptilimountains meet the pumped up steroid-o-saurs of today. It's tempting to think that the old guys wouldn't last five minutes, but they'd certainly have a significant weight advantage. Maybe a Robinson-esque apatosaur could be deployed like a rolling log down a hillside, squishing countless little feathery theropods on the way down.

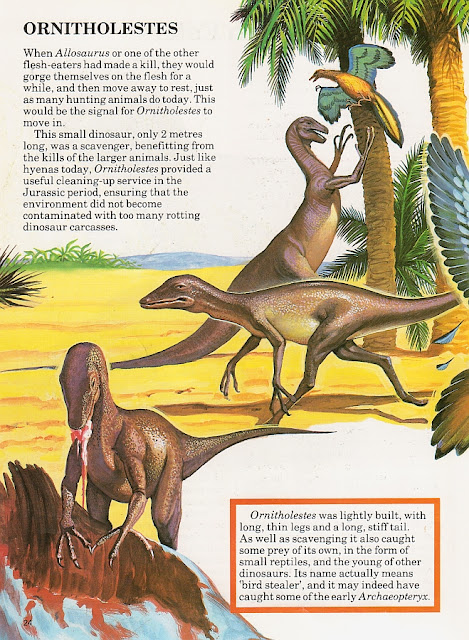

Speaking of which, Robinson was actually rather good at painting Archaeopteryx, too; not perfect (the feathers are occasionally attached to the wrong digits), but they at least look like not-quite-birds, rather than little lizard gits with scaly dragon faces and tiny 'extra fingers' (a trope I like to call 'Wings...but with hands!'). See the individual in the image above, and corresponding close-up below. Note that the contour feathers blend with one another convincingly, rather than sticking out all over the place and making a mess.

There are many more Robinson lovelies in TAoD, not least this painting of fighting pachycephalosaurs. I remember this one particularly vividly from my childhood, and I believe that's down to the unnervingly lifelike, disconcertingly staring face of the individual in the foreground. It's a remarkable piece, with the animal's nodule-encrusted visage threatening to have your eye out; a real case of dinosaurs being in your face. It's an alien, otherworldly creature made remarkably real. It's perhaps also worth noting that the pronounced musculature and generally quite svelte appearance of the animals is unusually progressive for '70s-era Robinson. And the sky's nice, too.

Equally fetching is this lovely painting of an Ichthyostega pair in their steaming, swampy home. Unfortunately, a great deal of it is covered up with a dirty great text box, in which author David Lambert claims that animals couldn't see any reason to live on dry land; they just reached the shore, shrugged their incipient shoulders, and sunk back into the bog. The lousy layabouts. You're doing nothing for vertebrate evolution, you squishy-skinned slackers!

While I remain a big fan (in spite of the occasional...unpleasantness), there's more to TAoD than just Bernard Robinson. John Francis and Ross Wardle are the other two illustrators, although individual pieces aren't credited (or signed, as with Robinson's), so unfortunately it's difficult to figure out who produced what. Almost as unfortunately, a lot of the illustrations also appeared in the earlier Dinosaur World, and I really did review that one too recently to start wheeling out repeats. Nevertheless, one tends to get a wider view of the reused illustrations in TAoD, so it's possible to see, for example, just what that hungry T. rex was chasing. Gangly, anachronistic hadrosaurs, as it turns out.

Hurrah. There's also enough new stuff to pad out this post, including the below Triceratops, depicted charging through dirt with a wonderful momentum and carefully applied flying mud splatters. When compared with other animals in this book, the Triceratops' anatomy is really rather good, with the artist making effective use of the unusual perspective. On the other hand, this does make it all the more cringe-inducing that the animal's 'eyebrow' horns are shown protruding from its frill. Gah...

As if to underline my point about the Triceratops actually being pretty decent (but shame about the face), it shares a double-page spread with this bizarre retro ankylosaur, complete with stunted tail, pangolin claws and grumpy turtle mug. Seemingly, relatively accurate ankylosaurs only entered popular books en masse in the late 1980s, and then it was because they were all copies of John Sibbick's Euoplocephalus from the Norman encyclopaedia. As with the freaky giraffoid Barosaurus, freaky woodlouse ankylosaurs were an artistic meme that long outlasted their sell-by date.

The book is topped off by a marvellous 'dinosaur parade', featuring some excellent watercolour work and amusingly shifty-looking dubious-o-saurs. Leonard Nimoy is wisely running away, of course, but it's not the disinterested Tyrannosaurus he needs to worry about - not when that Stegosaurus looks so utterly furious. While ol' plateback might be too slow to catch him now, it knows exactly where he lives, and will shuffle back there and hide in the bushes until the following morning, when Nimoy will find himself brutally thagomised on his doorstep. Stegosaurus is patient. Stegosaurus always wins.

Paul Heaston's Facebook comment is also worth mentioning here.

"Dinosaurs? In the Shire?"

And finally...does anyone know the origin of the Gangly Dork Parasaurolophus? We've already seen them once in this book, of course, but the below is particularly superb example of this rather baffling meme. For a long time, Parasaurolophus - even moreso than other hadrosaurs - was depicted as having a highly upright carriage, noodle neck and piffling feeble forelimbs for no good reason whatsoever. Presumably just another case of artists copying artists copying artists.

And that's your lot! Coming up soon...a review of All Your Yesterdays. Hopefully.