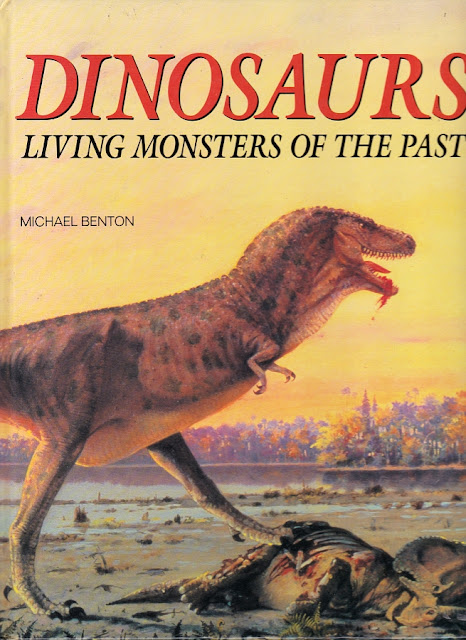

Here's a book that I bought some months ago, only for it to disappear under a pile of quirkier, more remarkable tomes acquired from eBay. It's very typical early '90s fare (1993 specifically), authored by palaeontologist Michael Benton (who writes a popular book on dinosaurs aimed at a young audience every morning over breakfast) and illustrated by a number of artists, but mostly John Sibbick. However (and quite apart from the fantastic cover), I may have unfairly overlooked it. The Sibbick pieces on their own are worthy of a VDA post, and it's exactly those that I'll be looking at here.

Showing posts with label John Sibbick. Show all posts

Showing posts with label John Sibbick. Show all posts

Wednesday, February 24, 2016

Thursday, February 11, 2016

Vintage Dinosaur Art: Dinosaurs, National Geographic, January 1993 - Free poster bonus!

Those of you with a nostalgic fondness for the January '93 issue of National Geographic featured in the last post will likely recall the free poster to be found within. Happily, the copy of the magazine that I bought on eBay arrived complete with said freebie, in all of its glossy, double-sided 1990s glory. One side of the poster displays a map of North America in the Late Cretaceous, surrounded by groups of Late Cretaceous dinosaurs illustrated by John Sibbick; the other features 'Dawn on the Delta', a lovely panorama starring Anchiceratops and painted by Robert Giusti. Let's look at the Sibbick side first of all, and specifically this delightful group of hadrosaurs, because the whole thing won't fit in my scanner and my photographs of it are terrible.

Tuesday, October 20, 2015

Vintage Dinosaur Art: Purnell's Find Out About Prehistoric Animals - Part 2

Because I can't in all good conscience review a book with 'Prehistoric Animals' in the title and only cover the dinosaurs, behold various non-dinosaurs from Purnell's 1976 guide to long-dead beasties. (There's also a tiresomely long section on how MAN evolved to DOMINATE the Earth by being SUPERIOR to the other creatures by virtue of having a large brain, dextrous hands, and other noted attributes of MANLINESS. It's as 1970s as an brightly-coloured Ford Cortina, which you'd be far better off looking at. Here you go.) Where better to start than with a pterosaur being munched? Stupid pterosaurs.

Labels:

1970s,

John Sibbick,

purnell,

vintage dinosaur art

Monday, October 5, 2015

Vintage Dinosaur Art: Purnell's Find Out About Prehistoric Animals

Not for the first time, here's a fantastic 1970s book on prehistoric animals from Purnell, purveyors of fine model photography and anachronistic pop-up battles. Find Out About Prehistoric Animals is considerably more hefty than any Purnell to previously feature on this blog, and it's gloriously packed full of wonderfully retro illustrations from a number of artists. While individual pieces aren't credited, we are at least informed that the artists included Eric Jewell Associates, Illustra, John Barber, Angus McBride, Sean Rudman, Dan Escott, Colin Rattray, Vanessa Luff, Gerry Embleton, Phil Green, George Underwood and - oh yes - John Sibbick. Nine years before even the Normanpedia. Blimey.

Labels:

1970s,

John Sibbick,

purnell,

vintage dinosaur art

Saturday, May 9, 2015

Vintage Dinosaur Art: The Superbook of Dinosaurs

Given the despairingly awful recent parliamentary election result in the country in which I happen to live, it's a good thing that Vintage Dinosaur Art is on hand to cheer everyone up. Especially as I've been quite looking forward to writing about this one - it might mostly be a fairly typical book of the period (1985), but it features a few tropetastic pieces that definitely raise a smile. Furthermore, much of the art is actually pretty good - at least at a technical level - and there are one or two early pieces from now well-established names. It's no less than The Superbook of Dinosaurs!

Labels:

1980s,

bernard robinson,

John Sibbick,

vintage dinosaur art

Thursday, November 27, 2014

Vintage Dinosaur Art: WHEN DINOSAURS RULED THE EARTH

With 1980s-style dinosaurs once again grabbing everyone's attention, thanks to the recent trailer for the long-delayed instalment of a certain cinematic franchise, it's only fitting that my latest book is a seminal specimen from the era. Hailing from around the same time as the Normanpedia,WHEN DINOSAURS RULED THE EARTH (which absolutely must be written in all-caps) sees Norman and Sibbick team up again, but this time the results are a little more fun (while avoiding anachronistic humans and dinosaurs made up by Ray Harryhausen). The cover says it all.

Tuesday, October 22, 2013

Royal Dinostamps

If you're a Briton (like me), then you'll no doubt have heard that the Royal Mail...was privatised recently, according to Prime Directive 2 of the inordinately wealthy neoliberal androids who run the country. But don't despair! Or rather, do despair, but also pay heed to this welcome distraction. For the Royal Mail also recently issued a new set of prehistoric animal-themed stamps, illustrated by John Sibbick. There are ten to collect, each one featuring a Mesozoic creature discovered in the UK (only six of them actually feature dinosaurs).

The rather, er, mixed reaction to these stamps in Social Media Land only made me more intrigued, so off I popped to the Royal Mail website to stuff a little more cash into the foul capitalists' pockets (by which I mean, I ordered a set).

The rather, er, mixed reaction to these stamps in Social Media Land only made me more intrigued, so off I popped to the Royal Mail website to stuff a little more cash into the foul capitalists' pockets (by which I mean, I ordered a set).

|

| Remember, all images are copyrighted. So don't go making hipster t-shirts out of them or anything. They'll find you. |

Monday, March 4, 2013

Vintage Dinosaur Art: De Oerwereld van de Dinosauriërs - Part 4

In common with so many popular dinosaur books, and in spite of its title, De Oerwereld van de Dinosauriërs (aka Dinosaurs: a Global View) actually dedicates quite a number of pages - and indeed plates - to animals from the Palaeozoic that preceded the first dinosaurs by tens of millions of years. In fact, the book even gives over a great deal of room to synapsids. Not that I'm complaining, of course, as it means we get to enjoy even more stunning works of art than we would otherwise have done...like this one. (It's also a good excuse to keep the 'Vintage Dinosaur Art' title for this post, see.)

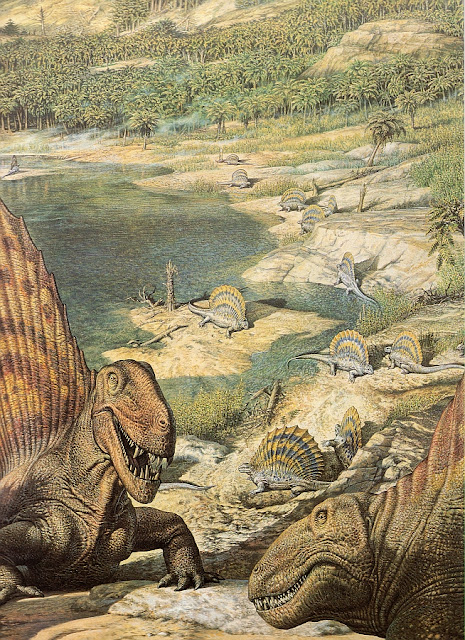

Dimetrodon is probably the most well-known Palaeozoic creature in popular culture, and is known to anachronistically frequent dinosaur movies, toy ranges and the like (and even appears in silhouette form on the wall of the Natural History Museum's 'Dino Store'. Oh yes, I noticed. Cheeky Dimetrodon). John Sibbick's depiction of the beast is perhaps my favourite piece of his that appears in this book. The foreground stars are stunning, of course, and the three-quarter view is perfect for emphasising the animal's deep, narrow skull, its sprawling posture and a general appearance that seems confusing and contradictory at first; it's no wonder that the term 'mammal-like reptile' has tended to stick.

That said, it's the wonderful backdrop here that really made me fall in love with the Permian all over again. The glorious vista, populated by a herd of the pin-headed sailback Edaphosaurus, effectively draws the viewer's gaze slowly inward, immersing them completely in this subtly alien world. And the water looks lovely.

Given its aforementioned popularity, it shouldn't be too surprising that Dimetrodon makes another appearance in this Doug Henderson piece. However, whereas Dimetrodon is typically shown hauling itself across the sun-parched earth, here Henderson depicts it taking to the water in pursuit of its prey - and why not? Partially concealed beneath the surface, the Dimetrodon here takes on a startling, bizarre silhouette - a jutting, knife-like fin trailing a vicious set of gaping jaws. It's easy to imagine Dimetrodon going for a dip fairly frequently, given the rich pickings offered in the form of amphibians like these Diadectes.

It's the lesser-known Early Permian gang! On the left, anyway. Dimetrodon might get all the glory, but this little lot are the unsung heroes of the period (indulgent in-joke, sorry). The style is unmistakably Sibbick, right down to the last preposterously miniscule warty detail on the adorable Cacops (foreground). This scene also features the ludicrously shrunken-headed synapsid Casea and, in the far background, the fearsome Varanops which, in spite of appearances, was also a synapsid. The forked tongue would appear to be Sibbick taking the monitor lizard analogy a little too far.

On the right, well, I've cheated; this mandible-disarticulating Doug Henderson piece actually depicts a still earlier world - that of the Late Carboniferous, over 310 million years ago. This piece is a spectacular summary of the age as one dominated by enormous, bizarre-looking plants, with Sigillaria looming imposingly from behind a tangled veil of tree ferns. The dramatically leaping animal in the foreground is Hylonomus, the earliest known definitive reptile. While I realise I gush about Henderson non-stop, this truly is one of his masterpieces; I only wish I had an enormous print of it to hang on my wall.

Moving on up to the Triassic, and Henderson provides us with one of the more memorable restorations of Postosuchus to feature in a popular book. Here, the sinister archosaurian macropredator adopts a nonchalant air as it tosses a young Desmatosuchus to the skies, perhaps with the aim of breaking off a few of those unpalatable spines. Yet another example of Henderson's superb and original compositions - a brilliant imagination to match his artistic flair. Gush gush gush. I hear his feet really smell*, though, which is important to take into consideration. Just remember that.

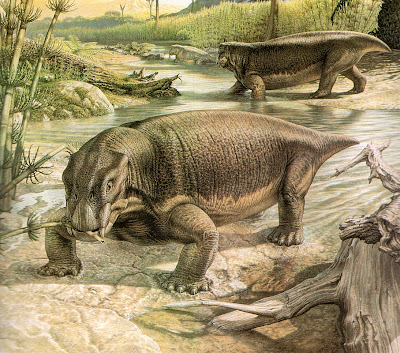

Lystrosaurus is perhaps best known for being a dumpy, herbivorous creature that nevertheless came to be the UNQUESTIONED MASTER OF THE EARTH...for a while, following the worst-ever mass extinction at the end of the Permian, an event so catastrophic that ITV's Saturday night schedule pales by comparison. (Sadly, no one has yet seen fit to make a film entitled 'When Lystrosaurus Ruled the Earth', in which herds of dopey dicynodonts slowly mill around a vast arid landscape in real time for three hours, set to an ever-so-arty minimalist soundtrack.)

Anyway, the top illustration, by Sibbick, makes for a charming profile of the creature with a typically lovely, peaceful ambience. The lower illustration, by Mark Hallett (he's back!), is a detail from a larger piece in which an unfortunate individual is being reduced to raw hamburger by a ravenous gang of Cynognathus. I can only apologise, again, for not being able to reproduce more of it here - however, this detail does show Hallett's remarkable, seemingly intuitive grasp of what makes a painted animal appear truly alive.

And finally...some ichthyosaurs. But wait, stifle your yawns at the back, for these are giant ichthyosaurs - Shonisaurus! The rather rotund restoration of the animal dates this picture a little now, but it remains astonishingly beautiful; the oceanic murk is realistic enough to be eerie, and the dappled sunlight on the backs of the animals is fantastically well observed.

All this without mentioning any peculiar ideas on the origin of birds...we may have to return...

*Not at all true.

Dimetrodon is probably the most well-known Palaeozoic creature in popular culture, and is known to anachronistically frequent dinosaur movies, toy ranges and the like (and even appears in silhouette form on the wall of the Natural History Museum's 'Dino Store'. Oh yes, I noticed. Cheeky Dimetrodon). John Sibbick's depiction of the beast is perhaps my favourite piece of his that appears in this book. The foreground stars are stunning, of course, and the three-quarter view is perfect for emphasising the animal's deep, narrow skull, its sprawling posture and a general appearance that seems confusing and contradictory at first; it's no wonder that the term 'mammal-like reptile' has tended to stick.

That said, it's the wonderful backdrop here that really made me fall in love with the Permian all over again. The glorious vista, populated by a herd of the pin-headed sailback Edaphosaurus, effectively draws the viewer's gaze slowly inward, immersing them completely in this subtly alien world. And the water looks lovely.

Given its aforementioned popularity, it shouldn't be too surprising that Dimetrodon makes another appearance in this Doug Henderson piece. However, whereas Dimetrodon is typically shown hauling itself across the sun-parched earth, here Henderson depicts it taking to the water in pursuit of its prey - and why not? Partially concealed beneath the surface, the Dimetrodon here takes on a startling, bizarre silhouette - a jutting, knife-like fin trailing a vicious set of gaping jaws. It's easy to imagine Dimetrodon going for a dip fairly frequently, given the rich pickings offered in the form of amphibians like these Diadectes.

It's the lesser-known Early Permian gang! On the left, anyway. Dimetrodon might get all the glory, but this little lot are the unsung heroes of the period (indulgent in-joke, sorry). The style is unmistakably Sibbick, right down to the last preposterously miniscule warty detail on the adorable Cacops (foreground). This scene also features the ludicrously shrunken-headed synapsid Casea and, in the far background, the fearsome Varanops which, in spite of appearances, was also a synapsid. The forked tongue would appear to be Sibbick taking the monitor lizard analogy a little too far.

On the right, well, I've cheated; this mandible-disarticulating Doug Henderson piece actually depicts a still earlier world - that of the Late Carboniferous, over 310 million years ago. This piece is a spectacular summary of the age as one dominated by enormous, bizarre-looking plants, with Sigillaria looming imposingly from behind a tangled veil of tree ferns. The dramatically leaping animal in the foreground is Hylonomus, the earliest known definitive reptile. While I realise I gush about Henderson non-stop, this truly is one of his masterpieces; I only wish I had an enormous print of it to hang on my wall.

Moving on up to the Triassic, and Henderson provides us with one of the more memorable restorations of Postosuchus to feature in a popular book. Here, the sinister archosaurian macropredator adopts a nonchalant air as it tosses a young Desmatosuchus to the skies, perhaps with the aim of breaking off a few of those unpalatable spines. Yet another example of Henderson's superb and original compositions - a brilliant imagination to match his artistic flair. Gush gush gush. I hear his feet really smell*, though, which is important to take into consideration. Just remember that.

Lystrosaurus is perhaps best known for being a dumpy, herbivorous creature that nevertheless came to be the UNQUESTIONED MASTER OF THE EARTH...for a while, following the worst-ever mass extinction at the end of the Permian, an event so catastrophic that ITV's Saturday night schedule pales by comparison. (Sadly, no one has yet seen fit to make a film entitled 'When Lystrosaurus Ruled the Earth', in which herds of dopey dicynodonts slowly mill around a vast arid landscape in real time for three hours, set to an ever-so-arty minimalist soundtrack.)

Anyway, the top illustration, by Sibbick, makes for a charming profile of the creature with a typically lovely, peaceful ambience. The lower illustration, by Mark Hallett (he's back!), is a detail from a larger piece in which an unfortunate individual is being reduced to raw hamburger by a ravenous gang of Cynognathus. I can only apologise, again, for not being able to reproduce more of it here - however, this detail does show Hallett's remarkable, seemingly intuitive grasp of what makes a painted animal appear truly alive.

And finally...some ichthyosaurs. But wait, stifle your yawns at the back, for these are giant ichthyosaurs - Shonisaurus! The rather rotund restoration of the animal dates this picture a little now, but it remains astonishingly beautiful; the oceanic murk is realistic enough to be eerie, and the dappled sunlight on the backs of the animals is fantastically well observed.

All this without mentioning any peculiar ideas on the origin of birds...we may have to return...

*Not at all true.

Tuesday, February 12, 2013

Vintage Dinosaur Art: De Oerwereld van de Dinosauriërs - Part 3

We haven't finished with De Oerwereld yet - not while I can still harvest more posts from it. Before proceeding, be sure that you've already ogled Part 1: Theropods and Part 2: Sauropodomorph Boogaloo. This week it's the turn of assorted ornisthichians, starting with a stunning work of art that was turned into one of the best-loved palaeo-posters since before time began (I'm in an '80s sort of mood, you see).

Mark Hallett might just be my favourite palaeoartist, if not of all time, then definitely of the hyper-detailed, 'photorealistic' school. Plenty of artists have produced mind-boggling works that are technically superb, but can often feel rather staid, stately and a little lifeless. Hallett's true skill, beyond his already highly impressive technical ability, is in avoiding this. Although extremely detailed, there is a boldness, an energy in his work that is often missing from that of other 'photorealistic' artists. This hugely popular painting, of two fighting Triceratops, is certainly among his very best work - I can but apologise for only being able to provide details here, rather than the whole thing.

In such an action-packed scene, it's easy to miss the enormous care that Hallett has taken in detailing not only the animals, with their highly lifelike expressions and carefully researched anatomy, but the surrounding environment. In a Hallett piece, there will always be splashing water, crumbling earth, and vegetation being twisted and snapped. Like the other artists in this book, Hallett's work has aged remarkably well, and often any historical errors are virtually insignificant. In this case, for example, I'm pretty sure that the uniting of Triceratops' digits into a single elephantine 'paw' would be frowned upon these days...if anyone noticed.

Doug Henderson's work is frequently distinguished by its expert use of elaborate foliage, so it's interesting to see a piece like this, in which two drowned centrosaurs appear (at first glance) to be suspended in an ethereal void. There is a wonderful dreamlike quality here - we are strangers in this alien world, which belongs to the plesiosaur, itself heedless to the dramatic sight of the giant animals' bodies drifting idly by above. Equally, there is a beautiful melancholy, as in so much of Henderson's art...

...Like this, for example. In a lot of palaeoart, the animals will practically be jumping down our throats, as if they're putting on a show for us (it's almost possible to smell the popcorn). Instead, Henderson offers us furtive glimpses through the thick underbrush of a world that is as lush and filled with life as it is hostile and unwelcoming. Dinosaurs, so often depicted as the lords of the Earth, are typically hopelessly dwarfed by their surroundings. There's something so very real about it all.

Of course, it's not all Hallett and Henderson - there are also shots of superb models sculpted by Stephen Czerkas, which have themselves been remarkably influential (for example, check out some of Raul Martin's earlier stuff). Handily presented from every angle, it's possible to see that Czerkas has accurately given the animal sauropod-like columnar 'hands', something that people have seemingly never been able to get right.

Doug Henderson did stegosaurs too - of course he did. They're just way over there, and you'll have to clamber through the forest to catch a glimpse of them. One is reminded of forest elephants gathering at a lakeside clearing - big animals with an unlikely aptitude for remaining hidden. Here, the trees seem testament to the destructive power of a herd of huge herbivores - be they the stegosaurs themselves, or their considerably larger neighbours. Why, the dinosaurs are quite literally framed by the very destruction they leave in their wake. The background stegosaurs, exposed to the sun's glare, take on a ghostly and elegant quality that seems quite at odds with their lumbering, cumbersome appearance.

Speaking of lumbering and cumbersome...and thyreophorans...the book includes Hallett's rendition of the famously spiny ankylosaur, Saichania. It doesn't quite appear flat and wide enough, but is nevertheless imbued with Hallett's scarcely matched lifelike quality. Much of this is owed to the texture work - the animal's thorny armour glints and gleams menacingly, while its gnarled head appears solid enough to touch. It's possible to imagine running one's hand over its knobbly surface, right before having one's head stoved in by a high-velocity bony lump.

Much of the longevity of Hallett's work is owed to the fact that Hallett restored his animals in a way that was anatomically rigorous, while also avoiding the worst excesses of the 'dinosaur streamlining' that went on in the '70s and '80s. In fact, and while it's no William Stout zombie-o-saur, his Hypacrosaurus is unusual in having a rather shrink-wrapped head and pencil-thin neck. Nevertheless, it's very difficult to deny that it is an absolutely stunning piece of work, as per bloody usual. Bah.

And finally...the work of some upstart named John Sibbick. Here, some moronic Ouranosaurus are trying their very best to make a racket and upset Old Man Sarcosuchus, a world-weary soul who would just like to get some rest before he sets out once again to do battle with Suchomimus and what have you. Really, though, this is a lovely scene, with a beautifully well-observed river delta and an exquisitely painted gharial-zilla.

De Oerwereld van de Dinosauriërs will return! There's an awful lot of Palaeozoic art in this book that's begging to be shared, including some seldom-seen Sibbicks, alongside Henderson works so beautiful they'll move you to muted tears accompanied by a sad string soundtrack. We'll be back.

Mark Hallett might just be my favourite palaeoartist, if not of all time, then definitely of the hyper-detailed, 'photorealistic' school. Plenty of artists have produced mind-boggling works that are technically superb, but can often feel rather staid, stately and a little lifeless. Hallett's true skill, beyond his already highly impressive technical ability, is in avoiding this. Although extremely detailed, there is a boldness, an energy in his work that is often missing from that of other 'photorealistic' artists. This hugely popular painting, of two fighting Triceratops, is certainly among his very best work - I can but apologise for only being able to provide details here, rather than the whole thing.

In such an action-packed scene, it's easy to miss the enormous care that Hallett has taken in detailing not only the animals, with their highly lifelike expressions and carefully researched anatomy, but the surrounding environment. In a Hallett piece, there will always be splashing water, crumbling earth, and vegetation being twisted and snapped. Like the other artists in this book, Hallett's work has aged remarkably well, and often any historical errors are virtually insignificant. In this case, for example, I'm pretty sure that the uniting of Triceratops' digits into a single elephantine 'paw' would be frowned upon these days...if anyone noticed.

Doug Henderson's work is frequently distinguished by its expert use of elaborate foliage, so it's interesting to see a piece like this, in which two drowned centrosaurs appear (at first glance) to be suspended in an ethereal void. There is a wonderful dreamlike quality here - we are strangers in this alien world, which belongs to the plesiosaur, itself heedless to the dramatic sight of the giant animals' bodies drifting idly by above. Equally, there is a beautiful melancholy, as in so much of Henderson's art...

...Like this, for example. In a lot of palaeoart, the animals will practically be jumping down our throats, as if they're putting on a show for us (it's almost possible to smell the popcorn). Instead, Henderson offers us furtive glimpses through the thick underbrush of a world that is as lush and filled with life as it is hostile and unwelcoming. Dinosaurs, so often depicted as the lords of the Earth, are typically hopelessly dwarfed by their surroundings. There's something so very real about it all.

Of course, it's not all Hallett and Henderson - there are also shots of superb models sculpted by Stephen Czerkas, which have themselves been remarkably influential (for example, check out some of Raul Martin's earlier stuff). Handily presented from every angle, it's possible to see that Czerkas has accurately given the animal sauropod-like columnar 'hands', something that people have seemingly never been able to get right.

Doug Henderson did stegosaurs too - of course he did. They're just way over there, and you'll have to clamber through the forest to catch a glimpse of them. One is reminded of forest elephants gathering at a lakeside clearing - big animals with an unlikely aptitude for remaining hidden. Here, the trees seem testament to the destructive power of a herd of huge herbivores - be they the stegosaurs themselves, or their considerably larger neighbours. Why, the dinosaurs are quite literally framed by the very destruction they leave in their wake. The background stegosaurs, exposed to the sun's glare, take on a ghostly and elegant quality that seems quite at odds with their lumbering, cumbersome appearance.

Speaking of lumbering and cumbersome...and thyreophorans...the book includes Hallett's rendition of the famously spiny ankylosaur, Saichania. It doesn't quite appear flat and wide enough, but is nevertheless imbued with Hallett's scarcely matched lifelike quality. Much of this is owed to the texture work - the animal's thorny armour glints and gleams menacingly, while its gnarled head appears solid enough to touch. It's possible to imagine running one's hand over its knobbly surface, right before having one's head stoved in by a high-velocity bony lump.

Much of the longevity of Hallett's work is owed to the fact that Hallett restored his animals in a way that was anatomically rigorous, while also avoiding the worst excesses of the 'dinosaur streamlining' that went on in the '70s and '80s. In fact, and while it's no William Stout zombie-o-saur, his Hypacrosaurus is unusual in having a rather shrink-wrapped head and pencil-thin neck. Nevertheless, it's very difficult to deny that it is an absolutely stunning piece of work, as per bloody usual. Bah.

And finally...the work of some upstart named John Sibbick. Here, some moronic Ouranosaurus are trying their very best to make a racket and upset Old Man Sarcosuchus, a world-weary soul who would just like to get some rest before he sets out once again to do battle with Suchomimus and what have you. Really, though, this is a lovely scene, with a beautifully well-observed river delta and an exquisitely painted gharial-zilla.

De Oerwereld van de Dinosauriërs will return! There's an awful lot of Palaeozoic art in this book that's begging to be shared, including some seldom-seen Sibbicks, alongside Henderson works so beautiful they'll move you to muted tears accompanied by a sad string soundtrack. We'll be back.

Tuesday, January 15, 2013

Vintage Dinosaur Art: De Oerwereld van de Dinosauriërs - Part 2

That's right - it's time for another look at the best palaeoart of the 1980s, as presented in De Oerwereld van de Dinosauriërs, also known as Dinosaurs: a Global View. I'm sure all of you - literally all of you, every last individual reading this blog- eagerly lapped up the last installment, but I'll link you back to it as a formality. Onwards!

As usual, I've been forced to cut certain images up into chunks due to the small size of my scanner, so please take note that this is merely the right half of Hallett's stunning depiction of Dicraeosaurus. Out of all the artists working in the 1980s, it is perhaps Hallett's work that has best stood the test of time scientifically; with a few minor tweaks, many of his 1980s paintings would pass muster today. Of course, they are also artistic achievements to match the classic palaeoart greats, as evidenced upon closer examination of this image. One is so impressed by the majesty of these huge creatures, it's easy to miss such details as the 'waterlines' on their hides, and the beautifully rendered sky.

In the background, it's possible to see Hallett's experiments with sauropod posture (notice the individual on the left). It's a wonderful depiction of sauropods happily going about their business, and quite possibly my favourite spread in the entire book.

As I noted last time, Henderson's work serves as an effective contrast to Hallett's in the context of this book. Whereas Hallett's is more immediate and features the animals in sharp focus, Henderson often obscures them in shadow, vegetation, or both. One of his greatest strengths is in using light effectively to both draw the viewer into a scene, and invoke a strong emotional response. Here, the bunny-handed allosaurs may rudely stick out to the 21st-century dinosaur enthusiast, but it doesn't matter. We are invited to imagine this Diplodocus' story, and what might happen between it and the skulking predators. Unlike Hallett and others, Henderson rarely depicts a fight in mid-swing - rather, he is concerned with the before and after.

Of course, when all is said and done, what you really want is BLOOD - never mind all that artsy-fartsy nonsense. Proving that sauropods are perfectly capable of defending themselves, here we see Shunosaurus performing uninvited, impromptu dentistry on an allosaur (most likely Yangchuanosaurus). However, if you are quite sick of violent palaeoart, then you are invited to inspect the carefully considered anatomy of the animals and their beautifully detailed footprints. Everyone loves a footprint.

Again, as previously noted (whaddaya mean, I've run out of things to say?), Henderson's art frequently exhibits a melancholy that is vanishingly rare, if not unique in palaeoart. Here it is evoked by the jagged forms of the rotting trees in the foreground, the furious, stormy sky, and the fact that the sauropods kinda have sad faces. Don't they, though? I mean, it's enough to make you want to hug one of their massive scaly legs, or perhaps offer them a mug of hot chocolate with marshmallows and cream. They're Patagosaurus, by the way, an animal that resembled the more famous Cetiosaurus.

Even if you think you haven't seen Mark Hallett's Crossing the Flat before, you definitely have. It's a bona fide palaeoart classic; naturally, it is reproduced in the book as a double-page spread. As such, I can only present a detail here (the calf and the mother's neck - Mamenchisaurus was absurd), although I have featured the whole thing once before. It's the sort of painting that, should people ever ask you why you find dinosaurs so bloody fascinating, you can press their noses against and say simply "THIS".

The latest biomechanical work has revealed that Plateosaurus almost certainly wasn't ever a quadruped, but, again, that hardly tarnishes one's appreciation of this lovely scene. Although only the left half is shown here, it hopefully gives a suitable flavour of this typically Hendersonian work - a marvelously tranquil portrayal of a wandering herd. Once again, the viewer is placed in a realistically detached position, and in this case is even being addressed by a glancing plateosaur (or so it appears), which as in all of Henderson's work greatly enhances the feeling of wandering, alone, in the Mesozoic. You might not last that long, but at least you'd see something as glorious and moving as this before being shredded into little pieces by a mob of voracious Coelophysis.

I didn't feature any Sibbick last time. Admittedly, Sibbick's work is very much in the minority in this book, but nevertheless this should redress the balance. This particular piece - a ceratosaur shouting some obscene insults at some trumped-up brachiosaur - has featured in a number of different publications, among them The Ultimate Dinosaur Book, a favourite from my childhood. Many have questioned what, exactly, the horned one is hoping to achieve in facing such a vastly bigger adversary; indeed, the UDB noted that it was 'unlikely' that a puny ceratosaur would ever pick on an adult brachiosaur. However, one doesn't have to interpret the scene in this way - it could be that the ceratosaur has been disturbed by the brachiosaur's heffalumpian tramplings, and is giving the big lug a piece of its mind before reluctantly moving on. And if that doesn't convince you, just look at that pterosaur's face. Oh my, what a face.

Next week: something different! De Oerwereld van de Dinosauriërs will return, but variety is the nutmeg of existence, and all that. Perhaps some more Ely Kish, perhaps an obscure 1980s pop-up book...we'll see.

As usual, I've been forced to cut certain images up into chunks due to the small size of my scanner, so please take note that this is merely the right half of Hallett's stunning depiction of Dicraeosaurus. Out of all the artists working in the 1980s, it is perhaps Hallett's work that has best stood the test of time scientifically; with a few minor tweaks, many of his 1980s paintings would pass muster today. Of course, they are also artistic achievements to match the classic palaeoart greats, as evidenced upon closer examination of this image. One is so impressed by the majesty of these huge creatures, it's easy to miss such details as the 'waterlines' on their hides, and the beautifully rendered sky.

In the background, it's possible to see Hallett's experiments with sauropod posture (notice the individual on the left). It's a wonderful depiction of sauropods happily going about their business, and quite possibly my favourite spread in the entire book.

As I noted last time, Henderson's work serves as an effective contrast to Hallett's in the context of this book. Whereas Hallett's is more immediate and features the animals in sharp focus, Henderson often obscures them in shadow, vegetation, or both. One of his greatest strengths is in using light effectively to both draw the viewer into a scene, and invoke a strong emotional response. Here, the bunny-handed allosaurs may rudely stick out to the 21st-century dinosaur enthusiast, but it doesn't matter. We are invited to imagine this Diplodocus' story, and what might happen between it and the skulking predators. Unlike Hallett and others, Henderson rarely depicts a fight in mid-swing - rather, he is concerned with the before and after.

Of course, when all is said and done, what you really want is BLOOD - never mind all that artsy-fartsy nonsense. Proving that sauropods are perfectly capable of defending themselves, here we see Shunosaurus performing uninvited, impromptu dentistry on an allosaur (most likely Yangchuanosaurus). However, if you are quite sick of violent palaeoart, then you are invited to inspect the carefully considered anatomy of the animals and their beautifully detailed footprints. Everyone loves a footprint.

Again, as previously noted (whaddaya mean, I've run out of things to say?), Henderson's art frequently exhibits a melancholy that is vanishingly rare, if not unique in palaeoart. Here it is evoked by the jagged forms of the rotting trees in the foreground, the furious, stormy sky, and the fact that the sauropods kinda have sad faces. Don't they, though? I mean, it's enough to make you want to hug one of their massive scaly legs, or perhaps offer them a mug of hot chocolate with marshmallows and cream. They're Patagosaurus, by the way, an animal that resembled the more famous Cetiosaurus.

Even if you think you haven't seen Mark Hallett's Crossing the Flat before, you definitely have. It's a bona fide palaeoart classic; naturally, it is reproduced in the book as a double-page spread. As such, I can only present a detail here (the calf and the mother's neck - Mamenchisaurus was absurd), although I have featured the whole thing once before. It's the sort of painting that, should people ever ask you why you find dinosaurs so bloody fascinating, you can press their noses against and say simply "THIS".

The latest biomechanical work has revealed that Plateosaurus almost certainly wasn't ever a quadruped, but, again, that hardly tarnishes one's appreciation of this lovely scene. Although only the left half is shown here, it hopefully gives a suitable flavour of this typically Hendersonian work - a marvelously tranquil portrayal of a wandering herd. Once again, the viewer is placed in a realistically detached position, and in this case is even being addressed by a glancing plateosaur (or so it appears), which as in all of Henderson's work greatly enhances the feeling of wandering, alone, in the Mesozoic. You might not last that long, but at least you'd see something as glorious and moving as this before being shredded into little pieces by a mob of voracious Coelophysis.

I didn't feature any Sibbick last time. Admittedly, Sibbick's work is very much in the minority in this book, but nevertheless this should redress the balance. This particular piece - a ceratosaur shouting some obscene insults at some trumped-up brachiosaur - has featured in a number of different publications, among them The Ultimate Dinosaur Book, a favourite from my childhood. Many have questioned what, exactly, the horned one is hoping to achieve in facing such a vastly bigger adversary; indeed, the UDB noted that it was 'unlikely' that a puny ceratosaur would ever pick on an adult brachiosaur. However, one doesn't have to interpret the scene in this way - it could be that the ceratosaur has been disturbed by the brachiosaur's heffalumpian tramplings, and is giving the big lug a piece of its mind before reluctantly moving on. And if that doesn't convince you, just look at that pterosaur's face. Oh my, what a face.

Next week: something different! De Oerwereld van de Dinosauriërs will return, but variety is the nutmeg of existence, and all that. Perhaps some more Ely Kish, perhaps an obscure 1980s pop-up book...we'll see.

Monday, January 7, 2013

Vintage Dinosaur Art: De Oerwereld van de Dinosauriërs - Part 1

Many of you are sure to recognise this one - its original English title was Dinosaurs: a Global View. The Dutch title - De Oerwereld van de Dinosauriërs - translates to something like 'the primordial/primeval world of the dinosaurs', which might sound a little more hackneyed (and possibly cheesy), but in this case actually sets the tone perfectly. If any triumvirate of artists was truly capable of transporting the viewer back to the Mesozoic, it would have to be Hallett, Sibbick and Henderson. What a team!

Originally published in 1990, with this Dutch edition arriving in 1993, most (if not all) of the artwork in this book dates from the preceding decade. Given the amount of, shall we say, ill-informed art that came out of that decade, it's easy to forget the sheer quality of the work being produced by the top-flight palaeoartists of the time (especially if your peculiar hobby is reviewing old dinosaur books for a certain blog). One could pluck any one of the plates from this book and it would be worthy of hanging in a hall and charging an entry fee to see.

As I did previously with the likes of Life Before Man, I'll endeavour to cover a reasonable amount in a handful of blog entries, until such a point when everyone's bored, or I'm threatened by somebody's lawyer. The book's chapters are essentially ordered chronologically through the Mesozoic, but I hope you don't mind me theming my posts around different groups of animals. This week - theropods! (Oh, and if you were wondering, the second-hand section on the first floor of the branch of De Slegte in Apeldoorn is an absolute treasure trove. I'm going back there for another book...)

Mark Hallett's Staurikosaurus seems a good place to start - not only does it deal with a Triassic subject, but is an excellent showcase for Hallett's mastery of the many subtleties that make a restored animal appear lifelike. Intricate details such as the stretching and sagging skin around the animal's limbs, the soft tissues in and around the mouth, and the reflection of light on its scales add up to create a quite uncanny, not to mention very beautiful, portrait of this 'primitive' theropod. I remember a jobbing illustrator's knock-off of this piece appearing in Dinosaurs! magazine back in the day, but of course I didn't realise it was a copy until very recently. Seeing the original after all those years was a revelation.

Unfortunately, my rather small and rubbish scanner can't possibly do justice to a lot of these pieces, and I did deliberate over whether to leave this particular one out. However, in the end I simply couldn't resist sharing at least a small part of it. Therefore, may I present a detail from Doug Henderson's jaw-dropping Coelophysis scene. Henderson is most famous for developing a style in which prehistoric animals are mere components of a much wider, usually stunningly rendered landscape, and so it is here. Although this fragment doesn't show it, this scene is utterly dominated by a gigantic, fallen tree bridging the river, and overshadowed by the branches of another (standing) tree. In the context of the whole piece, the Coelophysis appear tiny and vulnerable parts of an ecosystem on a colossal scale, their swarming numbers melting into the central river. Simply a masterpiece, and one of many.

Back to Hallett, and here two Dilophosaurus struggle over an unfortunate Scutellosaurus. The animals here have a very different 'feel' to the Staurikosaurus - although equally lithe and sleek, their skin appears tougher and more leathery as the result of masterful texturing. It's a violent scene, the likes of which have become something of a palaeoart cliché now, but again displays a superb attention to small details - in terms of the animals' anatomy (check out those legs), their interaction with the surrounding environment, and the environment itself.

Henderson's work is often imbued with a melancholic quality that's very unusual for palaeoart. The monochrome helps, of course, but the composition here is also key. The skulking Ceratosaurus, its back turned to the viewer, displays an air of indifference in spite of the hulking carcass of the sauropod, which cleverly blends into the landscape. A gnarled tree with bare branches and a fallen log frame the animals in the centre. It's haunting - and how many artworks featuring Mesozoic dinosaurs can you say that about?

In addition the illustrations, the book contains a small number of photographs of models sculpted by Stephen Czerkas. The scaly skin of this Deinonychus has certainly aged it now, but its intricate detailing and lifelike quality still impress. Also of note is the arrangement of the hands, with the palms facing correctly inward and folded down (although not back against the arm, as in modern birds). It's remarkably prescient for the time.

I'm running out of superlatives with which to describe Henderson's work. Instead, you can just picture me gawping pathetically, a sliver of drool descending slowly from the left edge of my gaping cakehole. (I'd include a photograph, but I think we'd lose readership.) Regardless, this scene depicts Albertosaurus - not chasing or biting or being stabbed in the guts by anything, but simply taking a leisurely stroll through a stupendously beautiful Hendersonian forest. It's classic Henderson. Niroot remarked how much Henderson's work reminded him, in terms of composition in particular, of Oriental painting. Whether or not Henderson really was influenced by Oriental painting I don't know, but it's certainly lovely to think so.

Speaking of things that look lovely, here's something that really doesn't - Czerkas' Carnotaurus. However, that's only because the animal itself was such a pug-faced weirdo, and is not a comment on Czerkas' sterling sculpting skills. Certain very minor details (the hands) would not be regarded as accurate today, but overall it has aged remarkably well, and (again) has a definite likelike quality. The animal appears pleasingly bulky and fleshy, although not excessively so, and exudes a certain predatory menace.

Although it is seemingly quite rare for Henderson to produce anything as conventional as a scene of predation, he naturally manages to excel at them nonetheless. Here, the familiar tyrannosaur Tarbosaurus launches an attack against the hadrosaur Saurolophus. Against the greens and blues of the hadrosaurs and sunlit river, the vibrant red head of the theropod is a startling focal point. Water was another Henderson specialty, and here it is possible to get a sense of the deceptive power in the flow of the river, as the individual at the bottom right struggles gallantly upstream. In the context of this book, the often quite detached, one might say 'peaceful' and painterly quality of Henderson's work contrasts effectively with the more visceral and immediate quality of Hallett's, and they compliment each other perfectly.

And finally...this is perhaps the most unusual piece in the book and, surprise, it features Tyrannosaurus. If any readers could inform me as to the exact age of this one I'd be very grateful, as it seems to me to be a little anachronistic, and it wouldn't surprise me if it was one of his older pieces. It's gorgeously painted, of course, but the tyrannosaurs have a peculiarly crocodilian vibe and rather long tails, both of which remind me very much of 1970s palaeoart. There's also that Pteranodon, which is...odd.

As for those hornlets over the eyes - could the tyrannosaur in that movie trace that particular feature of its now instantly recognisable appearance back to this painting...?

There's more to come from De Oerwereld van de Dinosauriërs! Please do come back next week, on Monday, or maybe a bit later, depending on whether or not I pull my finger out.

Originally published in 1990, with this Dutch edition arriving in 1993, most (if not all) of the artwork in this book dates from the preceding decade. Given the amount of, shall we say, ill-informed art that came out of that decade, it's easy to forget the sheer quality of the work being produced by the top-flight palaeoartists of the time (especially if your peculiar hobby is reviewing old dinosaur books for a certain blog). One could pluck any one of the plates from this book and it would be worthy of hanging in a hall and charging an entry fee to see.

As I did previously with the likes of Life Before Man, I'll endeavour to cover a reasonable amount in a handful of blog entries, until such a point when everyone's bored, or I'm threatened by somebody's lawyer. The book's chapters are essentially ordered chronologically through the Mesozoic, but I hope you don't mind me theming my posts around different groups of animals. This week - theropods! (Oh, and if you were wondering, the second-hand section on the first floor of the branch of De Slegte in Apeldoorn is an absolute treasure trove. I'm going back there for another book...)

Mark Hallett's Staurikosaurus seems a good place to start - not only does it deal with a Triassic subject, but is an excellent showcase for Hallett's mastery of the many subtleties that make a restored animal appear lifelike. Intricate details such as the stretching and sagging skin around the animal's limbs, the soft tissues in and around the mouth, and the reflection of light on its scales add up to create a quite uncanny, not to mention very beautiful, portrait of this 'primitive' theropod. I remember a jobbing illustrator's knock-off of this piece appearing in Dinosaurs! magazine back in the day, but of course I didn't realise it was a copy until very recently. Seeing the original after all those years was a revelation.

Unfortunately, my rather small and rubbish scanner can't possibly do justice to a lot of these pieces, and I did deliberate over whether to leave this particular one out. However, in the end I simply couldn't resist sharing at least a small part of it. Therefore, may I present a detail from Doug Henderson's jaw-dropping Coelophysis scene. Henderson is most famous for developing a style in which prehistoric animals are mere components of a much wider, usually stunningly rendered landscape, and so it is here. Although this fragment doesn't show it, this scene is utterly dominated by a gigantic, fallen tree bridging the river, and overshadowed by the branches of another (standing) tree. In the context of the whole piece, the Coelophysis appear tiny and vulnerable parts of an ecosystem on a colossal scale, their swarming numbers melting into the central river. Simply a masterpiece, and one of many.

Back to Hallett, and here two Dilophosaurus struggle over an unfortunate Scutellosaurus. The animals here have a very different 'feel' to the Staurikosaurus - although equally lithe and sleek, their skin appears tougher and more leathery as the result of masterful texturing. It's a violent scene, the likes of which have become something of a palaeoart cliché now, but again displays a superb attention to small details - in terms of the animals' anatomy (check out those legs), their interaction with the surrounding environment, and the environment itself.

Henderson's work is often imbued with a melancholic quality that's very unusual for palaeoart. The monochrome helps, of course, but the composition here is also key. The skulking Ceratosaurus, its back turned to the viewer, displays an air of indifference in spite of the hulking carcass of the sauropod, which cleverly blends into the landscape. A gnarled tree with bare branches and a fallen log frame the animals in the centre. It's haunting - and how many artworks featuring Mesozoic dinosaurs can you say that about?

In addition the illustrations, the book contains a small number of photographs of models sculpted by Stephen Czerkas. The scaly skin of this Deinonychus has certainly aged it now, but its intricate detailing and lifelike quality still impress. Also of note is the arrangement of the hands, with the palms facing correctly inward and folded down (although not back against the arm, as in modern birds). It's remarkably prescient for the time.

I'm running out of superlatives with which to describe Henderson's work. Instead, you can just picture me gawping pathetically, a sliver of drool descending slowly from the left edge of my gaping cakehole. (I'd include a photograph, but I think we'd lose readership.) Regardless, this scene depicts Albertosaurus - not chasing or biting or being stabbed in the guts by anything, but simply taking a leisurely stroll through a stupendously beautiful Hendersonian forest. It's classic Henderson. Niroot remarked how much Henderson's work reminded him, in terms of composition in particular, of Oriental painting. Whether or not Henderson really was influenced by Oriental painting I don't know, but it's certainly lovely to think so.

Speaking of things that look lovely, here's something that really doesn't - Czerkas' Carnotaurus. However, that's only because the animal itself was such a pug-faced weirdo, and is not a comment on Czerkas' sterling sculpting skills. Certain very minor details (the hands) would not be regarded as accurate today, but overall it has aged remarkably well, and (again) has a definite likelike quality. The animal appears pleasingly bulky and fleshy, although not excessively so, and exudes a certain predatory menace.

Although it is seemingly quite rare for Henderson to produce anything as conventional as a scene of predation, he naturally manages to excel at them nonetheless. Here, the familiar tyrannosaur Tarbosaurus launches an attack against the hadrosaur Saurolophus. Against the greens and blues of the hadrosaurs and sunlit river, the vibrant red head of the theropod is a startling focal point. Water was another Henderson specialty, and here it is possible to get a sense of the deceptive power in the flow of the river, as the individual at the bottom right struggles gallantly upstream. In the context of this book, the often quite detached, one might say 'peaceful' and painterly quality of Henderson's work contrasts effectively with the more visceral and immediate quality of Hallett's, and they compliment each other perfectly.

And finally...this is perhaps the most unusual piece in the book and, surprise, it features Tyrannosaurus. If any readers could inform me as to the exact age of this one I'd be very grateful, as it seems to me to be a little anachronistic, and it wouldn't surprise me if it was one of his older pieces. It's gorgeously painted, of course, but the tyrannosaurs have a peculiarly crocodilian vibe and rather long tails, both of which remind me very much of 1970s palaeoart. There's also that Pteranodon, which is...odd.

As for those hornlets over the eyes - could the tyrannosaur in that movie trace that particular feature of its now instantly recognisable appearance back to this painting...?

There's more to come from De Oerwereld van de Dinosauriërs! Please do come back next week, on Monday, or maybe a bit later, depending on whether or not I pull my finger out.

Thursday, December 6, 2012

Vintage Dinosaur Art: Creatures of Long Ago: Dinosaurs

Firstly, apologies for the lateness of this one - I missed the Monday deadline and then the other guys posted some material, and I thought it better that content be spread out over the week. Hopefully this book will be worth the wait - as nostalgia for some, and for everyone else as an interesting entry in the canon of one of the most well-known and respected palaeoartists. For my part, I had no idea it existed until very recently, and was instantly excited when I found it - pop-up Sibbick!

The illustrations in Creatures of Long Ago: Dinosaurs, which was published in 1988, show a marked improvement over those in the Norman encyclopedia from just three years prior. They demonstrate a stage in the evolution from Sibbick's earlier stodge-o-saurs to the altogether more active, muscular and modern-looking restorations of the '90s. Some quirks remain (including occasional peculiar leathery skin textures), but the improvements are obvious. Oh, and they picked a great cover, didn't they? Beautiful stuff. We're quite fond of chasmosaurs around here.

The book is comprised of six pop-up spreads, each of which features a snapshot of Mesozoic life in a particular time, although not in chronological order. All of the scenes feature North American animals, although whether or not this was intentional is not mentioned. While one or more large dinosaurs always provide the focus, each spread is crammed full of tiny, incidental detail, normally requiring some reader interaction to uncover (e.g. lifting a flap, pulling a tab), which really helps each piece come alive. It creates a sense of a truly three dimensional world populated by a large variety of animals just going about their business, even while monstrous dinosaurs duke it out in the foreground. The fiery orange sky in this opening spread is fantastic, immediately evoking a foreboding, primordial atmosphere.

This Ceratosaurus is a great way to kick things off (so to speak), as it appears to be literally stepping out of the page, which is a very immediate way of involving the reader in the Jurassic world being depicted. The perspective is exciting too, and shows off the vicious-looking claws on the animal's birdlike foot. Speaking of which, it's interesting to note the very birdlike scales on the tops of the toes, which are not present on the theropods in the Norman book, and perhaps hint that the artist was looking at these animals in a different light.

Peeling away some of the foliage reveals a Camptosaurus and, up in the corner, an Archaeopteryx. Quite what Archaeopteryx is doing in North America, I'm not sure - I suppose you just can't have a dinosaur book without it. Still, they are nice inclusions as I said.

Last week, I noted it was a shame that another pop-up book had missed the opportunity of having a brachiosaur's neck crane out from the page. Of course, that's exactly what they've done here - and it looks bloody marvellous. It's not all about having sauropods poking one in the eye, mind you - there are a great many subtle touches when opening the pages, from the Diplodocus lowering its neck on this spread, to the Stegosaurus raising its tail to fend off Ceratosaurus. The sauropods in this scene may look outdated now, but at least they were an improvement on the 1985 beasts - note for example that the Apatosaurus in the background no longer has such a 'brontosaur' (as in, the popular artistic representation) bodyplan.

If there's one animal that stands out as being peculiar even for the time, then it's this Allosaurus. Even in 1985, Sibbick gave the animal a skull that was the right sort of shape, with lacrimal horns - so what happened here? My pet theory is that this is actually a mislabeled Torvosaurus, based both on later Sibbick megalosaurs and the fact that Sibbick apparently knew what an Allosaurus head (basically) looked like. If that's true then it's still wrong, just not quite to the same degree. Er, which is much better. Yes.

These blue-headed Ornitholestes are interesting, and the pull tab feature demonstrates the wonderful attention to detail prevalent in this book - as the individual on the left moves across the page, it follows an undulating path so that it appears to be running. At the same time, a small pterosaur takes a diving arc from left to right. Little things, little things...

One of the more spectacular papercraft constructions in this book is undoubtedly this Tyrannosaurus, shown facing off (as it has a tendency to do) against a Triceratops family group, including a juvenile. Unlike the other scenes in the book, which are intended to be viewed head-on, this little diorama is best viewed by placing the book on a surface - after which the T. rex becomes a towering, imposing figure. It's also a huge improvement on the weirdo Norman-pedia version, with a far more Tyrannosaurus-like skull and a pair of impressive drumstricks; the very awkward tail is unfortunate but, then, these things happen sometimes when one's trying to make a pop-up book work. The Triceratops display an elephantine quality that was common in palaeoart well into the '90s, although the stumpy-horned baby is very cute.

The incidental details are especially easy to miss in this vertical scene, including this crafty Troodon, hiding furtively underneath a fern. Troodon is one of the few animals to appear in more than one scene, and it's always accompanied by a label that reads "Troödon". Troodon: the Motörhead of dinosaur genera.

Back in the late '80s and the '90s, it wasn't uncommon to see gangs of tiny dromaeosaurs taking on game that was bigger than them by ludicrous orders of magnitude. Admittedly, the Parasaurolophus concerned in this picture is described as juvenile, but it would still appear to be 'squishy time' for a lot of its pint-sized would-be predators. All such jesting aside, however, this is a seriously beautiful piece of art, with gorgeous foliage and scenery, and a highly effective use of the pop-up element both to create an illusion of depth and to add dynamism and excitement to the scene. The composition places the viewer at the centre of the action, giving them a Dromaeosaurus'-eye view.

More background detail: pulling a tab results in two Stegoceras engaging each other in combat. Always a firm palaeoart favourite.

This is probably my favourite spread in the book, simply because it gets you right up in a dinosaur's FACE...without being all cheesy and over-dramatic about it. The construction of the nest is quite ingenious too, with hatchlings emerging when tabs are pulled and flaps, er, flapped. While it's easy to be distracted by the huge centrepiece, there are plenty of lovely background details here, too - notice the lake with crocodiles and turtles to the left, and the pterosaurs flying overhead. From an anatomical perspective, these hadrosaurs mark a considerable improvement over their Norman-pedia forebears, particularly when it comes to such details as the forelimbs (note the hands and, particularly, the fingers).

Pulling tabs to the right and left result in the appearance of nest-bothering predators, with the concerned Maiasaura reacting accordingly; one lowers its head to shoo away a monitor lizard, while the other twists around to follow some scarpering Troodon.

The final scene focuses on an ornithomimosaur family, but still manages to cram in Chasmosaurus, Hypacrosaurus, Icthyornis, Hesperornis, the plesiosaur Elasmosaurus, and an unspecified mammal and snake. It's a glorious image of an entire community of animals, and it's an absolute pleasure to explore the page, uncovering new intricate details and moving parts (such as the foot-stamping chasmosaurs engaged in a dominance display). Soaking in every tiny facet of a piece is part of the enjoyment of appreciating Sibbick's work, but here there's extra fun to be had in peering under and around some parts of a pop-up piece to catch glimpses at others. Or maybe I'm just a gibbering man-child, I dunno. (And yes, those plesiosaurs do look very silly...like they're shouting 'Hey! Over here! Don't forget us!')

Yes, I'm a little bit in love with this book - far more so than any man in his 20s should rightly be with a kiddies' dinosaur pop-up book produced in the 1980s. What can I say? It's a gem.

Yes, I'm a little bit in love with this book - far more so than any man in his 20s should rightly be with a kiddies' dinosaur pop-up book produced in the 1980s. What can I say? It's a gem.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)