Apparently part of a series of 'Junior Illustrated Encyclopedias',

Prehistoric World dates from 1987 and features the work of a variety of artists, with text by palaeontologist Michael Benton. (It's also another one of the books that Jon Davies has let me borrow - thanks again Jon!) Unfortunately, it's not always possible to identify which artist was behind which piece - it's a shame to not be able to positively ID the artist behind the striking cover art, for example (although the style looks familiar). However, the book does feature some very interesting pieces by one artist in particular: Bernard Robinson.

Among dinosaur enthusiasts, Robinson is perhaps best known for illustrating the hugely popular

Ladybird dinosaur book (simply entitled

Dinosaurs). As I'm sure I've said a good dozen times by now, Robinson's particular skill was in creating stunningly realistic scaly skin textures. The animals' hides are rendered down to the tiniest detail, with each scale glistening perfectly in the scorching sunlight. By the late 1980s, however, Robinson's dinosaurs were taking on a strikingly anachronistic appearance, even if they remained beautifully painted.

Robinson's Ladybird dinosaurs were definitely of the old swamp-dwelling lizardy school, and it's tempting to assume that the illustrations in

Prehistoric World came later for a couple of reasons - firstly, some of the restorations appear notably more modern and secondly, the apparent inspirations behind some of the pieces seem to have changed. The weedy limbs and colour scheme on the above illustration are certainly consistent with Robinson's earlier work, but the strangely-shaped head and weird, leathery skin texture appear to owe a lot to 1980s

Sibbick. (I feel obliged to mention the 1980s

Spinosaurus too! Actually, it's a pretty good one. I should start a compendium of these.)

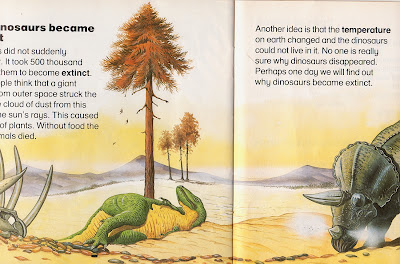

Out of all the Robinson illustrations in this book, the above is perhaps most noteworthy for deviating from what one might expect from the artist. The

Tyrannosaurus and

Triceratops look familiar enough (especially

the latter), and Robinson frequently depicted small(/ish) theropods as being notably more active than most of his other dinosaurs. However, the ankylosaur (labelled "

Ankylosaurus", but obviously

Euoplocephalus), with its active posture and elevated tail, marks a remarkable departure from Robinson's

earlier depictions of such animals, and even of large herbivorous dinosaurs in general. It too would seem to owe a lot to

Sibbick.

Why hello there, Mr Crocodile. Aren't you quite the handsome crocodile? Why, yes you are. It's very nice and all, but I've only really included this one for two reasons:

- Don't those birds look a lot like mallards?

- Michael Benton's caption makes me laugh. "The last days of the dinosaurs. Most of the animals shown here - the giant crocodile, frogs, birds, mammals [cropped out], plants and insects - survived the mass extinction. The dinosaurs alone in this scene were doomed." They were doomed, I tells ya! Doooomed!

Back to the task at hand. The

Iguanodon here are more classically Robinson, particularly in terms of skin texture; even so, although they are upright they lack the stiff, man-in-suit appearance of the

Ladybird incarnation. The

Hypsilophodon also show marked changes over earlier renditions, with alert postures, elevated tails and an overall Neave Parker-free look, while the freewheeling birds and adorable tortoise (mostly cropped out by the scanner, I'm afraid) add a pleasing believability to the scene. The sauropods, though, are bloody awful. Well, what can I say - I'm just caustic (for popularity's sake).

Robinson aside, the illustrations by other artists in this book tend to show the usual Burian and Zallinger influences (as above), which is a little yawnsome, and perpetuates a lot of the mistakes that Burian made through lack of available reference material. I am rather fond of the vibrant colours and painterly quality in the above piece, though, and the malevolent look on the face of the

Allosaurus as it prepares to spring out on its victim is just marvellous.

This Triassic scene is notable for including the theropod

Procompsognathus, which remains rather poorly understood. The restoration here is certainly rather odd, with its short neck, apparently near-vestigial arms and hands, and upright, tottering walk.

Because it's known from such fragmentary remains,

Procompsognathus doesn't often feature in art, although it did feature in Michael Crichton's

Lost World novel, in which it had a poisonous bite and ate dung or something. (I'll anticipate a comment here and point out that, yes, in the movie the Robert Bakk...Burke character did mistakenly refer to "

Compsognathus triassicus", conflating

C. longipes and

P. triassicus.) The

Plateosaurus in the background are modelling for early '90s mid-market dinosaur toy sculpts, and don't look too happy about it. Maybe they're not being paid enough.

And finally...déjà vu. Didn't we see these guys

a couple of weeks back? Yes indeed, it's yet more short-tailed, mast-necked

Barosaurus, with the obligatory inclusion of an individual craning its neck down towards the viewer. It's a meme that lasted at least a decade, although it's not one that I remember from my childhood - by then, it was all about the grumpy grey

Dorling Kindersley model Barosaurus, and of course art based on

that skeletal mount. Note that the wild weight guesses here refer to "Ultrasauros", another happy reminder that you're reading a dinosaur book from the 1980s.

I'll be back soon! Sorry about the delay this week - Real Life got in the way, although quite pleasantly for a change. There won't be such a delay before the next one, promise, and I've got more of Jon Davies' books to get through!