We have the nicest readers here at

Love in the Time of Chasmosaurs (most of the time), and Jon Davies just happens to be one of them. The scholarly Mr Davies, in a gesture of profoundly moving generosity, has allowed me to borrow a stack of much-loved dinosaur books from his youth so that I might gently poke fun at them. Thank you, Jon, you are a gentleman!

Of course, there was always going to be one book from among the selection that particularly caught my eye, and it'll be quite obvious from the image below why it had to be

The Complete Book of Dinosaurs. The cover alone is a source of unending joy - the fat sauropod is quite run-of-the-mill, but the warped theropod is a gloriously twisted, demented monstrosity. Having posted this image on the

LITC Facebook page yesterday, it attracted comparisons with the Xenomorph from

Alien and a Lovecraftian terror, both of which undoubtedly stem from the mismatched, disturbingly humanoid head. In fact, the front half looks like it belongs in a dinosaurian version of

Basket Case.

Thankfully, nothing

inside the book is quite this horrifying (which makes you wonder why they slapped such an awful thing on the cover). It's essentially a compendium of 1980s Beverly Halstead dinosaur books, with illustrations mostly from Jenny Halstead, but also occasionally Ross Wardle and Sol Kirby (the latter are taken directly from the abysmal second-rate

Zallinger knock-off

Dinosaurs of the Earth, which - wouldn't you know it - I reviewed for my first ever

LITC post). The late Bev Halstead (he died in 1991, but

still whispers in the ear of psychic Daily Mail drones) often had some rather eccentric ideas and held firm against the Dino Renaissance, but nonetheless is responsible for engaging many children with palaeontology - Darren Naish, for example, counts Halstead's

The evolution and ecology of the Dinosaurs as one of

his earliest dinosaur books.

Jenny Halstead, meanwhile, is a very accomplished artist who is

still around today - her website shows off some truly stunning work in the field of anatomical illustration and, more recently, pastels and oil painting. Having said all that, her dinosaurs, er, could have been better. The animals frequently look cartoonish, and body parts drastically change shape and proportion even in the same scene. The scenes featuring

Deinonychus (or "deinonychosaurus" as Beverly refers to them at one point) are particularly amusing, as the animals often have outsized googly eyes and comically exaggerated body parts - mostly the sickle claw, which often seems to subsume the entire toe.

Still, there certainly are some unusual scenes in this book. Every dinosaur artist has had a pop at illustrating a gang of

Deinonychus reducing a dopey herbivore to hamburger, but how many have shown the animals foraging for frogs in a lake? Happily, this painting is also one of the superior scenes in the book - the lily-covered lake looks lovely, and the flamingo(-like bird)s, while looking a little too close to their modern counterparts, add a pleasing touch of faunal variety. Most importantly, the look of the animals is consistent, and they make some sense anatomically (for the time, of course).

Things get weirder a bit further in. While making it clear that

Deinonychus was a highly agile and alert creature, Bev Halstead nevertheless maintains that "deinonychosaurs were cold blooded and needed the sun's heat". As such, we are treated to this truly strange image of juvenile dromaeosaurs sunning themselves on rocks like lizards, with their legs sprawling out to the sides...somehow. Note also how the individuals on the right hand side start to resemble those little squishy plastic finger puppets with wobbly arms. In fact, by far the best aspect of this painting is the very well observed blue-and-red lizard located in the bottom right hand corner, which I've cropped out because I am, in the end, heartless and cruel. And you're not here for lizards.

GODZILLA! Nah, it's just

Tyrannosaurus. But what's it doing here? Well, since the tubby waddling softy could only scavenge the kills of other dinosaurs, it evolved the astonishing ability to

travel backwards through time in order to meet its colossal energy needs by eating animals that had died close by in the distant past. In fairness, the little guys aren't described as being

Deinonychus but, well, come on now.

I'm particularly fond of the fellow in the bottom left, who looks very contented with his meal of stringy viscera. Bless.

Halstead's sauropods are fat - often grotesquely so - and definitely owe something to

Caselli's. The

Apatosaurus in the background of this scene looks like it would move a lot quicker if it rolled along sideways, while the babies are quite sluglike in their rotundity; all of them sport so many rolls of lard that they make

Eric Pickles look almost svelte by comparison. Noteworthy are the blunted, 'brontosaur' heads - indeed, the title of the book in which these illustrations first appeared is

A Brontosaur (or so it says here).

In spite of their stumpy, seemingly near-useless limbs (good only for pointing into the middle distance), a few of the baby brontosaurs manage to survive into adulthood, at which point the adult males must fight for dominance of the herd using their tails and...er...what

is that? A tumour? According to Bev Halstead,

"The two dinosaurs stood side by side, head to tail, for this was the way they would fight...The apatosaur that was stronger of perhaps younger would have the advantage. The bony lump gave him added force."

So there you go - it's a 'bony lump', and actually quite beneficial. Just don't ask why none of the other apatosaurs have one. This is the lucky deformed brontosaur that could.

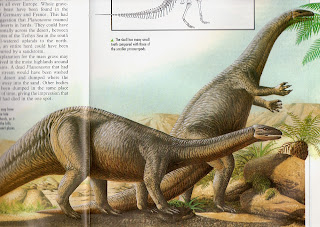

And finally...some rip-offs. These

Barosaurus look positively sleek and dynamic when compared with their bloated brontosaur brothers, and with good reason - they're ultimately all based on a Bakker drawing. In Bakker's original, the tail of one barosaur disappeared behind the body of another, which itself had a tail affected by foreshortening - thus giving rise to the artistic meme of the short-tailed

Barosaurus. In reality, of course, the animal would have resembled a slightly longer-necked

Diplodocus. Darren Naish (him again!)

covered all this back in

Tetrapod Zoology Mk II, and his article's well worth a read if you haven't done so already - you'll note that the animal in the background of the below scene owes much to the frightening 'Cox 1975'

Barosaurus as featured by Darren.

Come back next time for pterosaurs, Jenny Halstead-style!