There have been a great many 'dinosaur puzzle books' aimed at children over the years, the vast majority of which have been the sort of throwaway fare you'd find in a kiddies' goody bag alongside some cheap 'n' nasty plastic toys, largely devoid of any educational content. Dinosaurs! A Spot-the-Difference Puzzle Book (1995, no relation to anything involving David Norman) is a different matter entirely. Not only is it quite lavishly illustrated, the differences between each pair of pictures are used to highlight interesting aspects of dinosaur science. It's a wonderful conceit, even if the book takes a few strange turns along the way.

The artwork (by Charles Fuge) appears to be greatly influenced by the late Ely Kish and, in particular, William Stout. The approach is highly stylised, with an extremely vivid and saturated colour palette, and animals that (without being overly cartoonish) often have very expressive faces and, especially, eyes. The front cover gives a decent impression of what's to come. As befits a spot-the-difference book, there's a great deal going on in each scene, with all manner of animals joining in the fun/carnage (including more than a few anachronisms - but more on them later). It's all extremely compelling. In an approach that's rare in palaeoart as a whole - but very common in Stout's work - each scene has a border, often incorporating a couple of smaller frames that themselves form part of the spot-the-difference montage. Unfortunately, I've had to chop much of them off here (tiny scanner, see), but hopefully you'll still get a fair impression.

The first scene is a marine reptile jamboree, in which orca-coloured ichthyosaurs and albino plesiosaurs nibble each other playfully/brutally battle it out to the death. (While the text explains that the ichthyosaurs are tormenting the plesiosaur, it doesn't explain why - simply saying that the plesiosaur "is not their usual prey".) The croco-alike is Teleosaurus, just sneaking in an appearance while its more famous contemporaries steal centre stage yet again, while big-noggined weirdo Dimorphodon flies overhead. The oddly Devonian-looking fish is just oddly Devonian-looking. There's a lot of playful energy to the scene, and the ineffectual bite-off is pleasantly humorous, especially if one views it as a silly homage to all those 'elasmosaur v mosasaur' face-offs in palaeoart.

One of the most notable differences between this and its 'twin' image is the addition of a baby ichthyosaur in the bottom-left - author Steve Parker uses this as an opportunity to briefly explain live birth in ichthyosaurs, which is a fantastic example of how the spot-the-difference format is utilised in educating the reader. Neat.

Things start to get oddly anachronistic in this mixed Jurassic/Cretaceous scene, which throws Allosaurus, Brachylophosaurus/Tsintaosaurus (the former turns into the other as a difference to spot), Ornitholestes, Iguanodon and Apatosaurus into the same scene. Wuh? While the book explains that the animals are from different periods (and sometimes places), it seems like a strange decision to make - aren't there enough dinosaurs known from the Morrison formation without importing Cretaceous interlopers? Regardless, it's a very fun image, with an excellent variety of flashy saurian colour schemes going on, alongside a crocodilian who happens to resemble me on a particularly rough New Year's Day.

One of the 'differences' here is that Allosaurus is now drooling - which Parker uses as a launching point to discuss the likelihood of dinosaur drool (verdict: probable, based on modern reptiles). It's commendable that a common palaeoart trope is examined in this way, and example of the broadness of the book's look at the lifestyles and biologies of dinosaurs.

One of the most Stoutian of Fuge's creations is this wiry blue monstrosity, apparently representing none other than Coelurus itself - an animal seldom represented in art (perhaps because it's so poorly understood). The facial crustiness and glowering red eyes are sinister enough, but then there's the fact that every bony joint in the limbs seems to be on show - similar to Kish and Stout's skinny-o-saurs. Here, the straight tail of the middle Coelurus is a 'difference' (prompting commentary on theropod tails), along with the rat-like mammal being grasped by the background individual (invoking a note on mammalian evolution in the Mesozoic). The wee yellow fellas are Compsognathus, here in a classic '90s two-fingered form.

Could Diplodocus have ended up with its tongue stuck to a frozen tree? Such a question is surely raised by the above scene, in which a herd of the beasts amble around a winter wonderland, interrupted only by the occasional orange theropod carcass. This piece seems to reference a number of works of palaeoart (Hallett's Mamenchisaurus mother and calf, Bakker's barosaurs) without ripping them off directly. The human-like ribcage of the theropod (whither the gastralia?) is odd, but made up for by the depiction of these animals in such unusual climatic circumstances. Check out the cheeky mammal scoffing some dinosaur entrails, too. Stinkin' mammals.

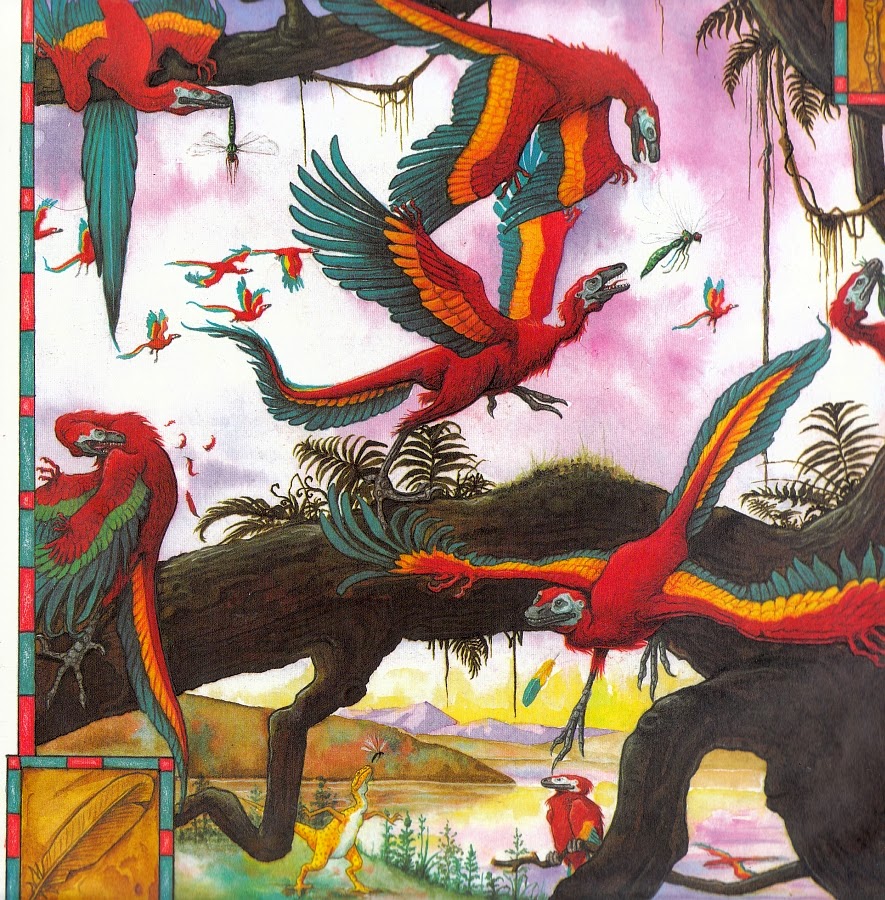

Over at Tricia's Obligatory Art Blog, Trish Herself has described feathered maniraptors with exuberant colour schemes as 'sparkleraptors' (a term I've nabbed a few times before). What would she make, then, of an Archaeopteryx apparently based on a scarlet macaw? While the colours are certainly very pretty (if a little unlikely), the awkward wing-hands aren't so much. Effin bird wings, man, how do they work? Still, I like this portrayal of a whole gathering of arboreal Archaeopteryx in different branch-based poses, including running, leaping and preening. Yes, there's the obligatory animal running along and snapping at a dragonfly (a trope that one of our readers lampooned recently), but at least it's doing it on a tree branch, rather than a patch of dirt with a single decorative cycad. There's a lot going on here, but the composition remains effective in drawing the eye from animal to animal, thus introducing the different behaviours.

The 'differences' include the chicken dance of the yellow fella at the bottom of the image. Parker uses this as cue to discuss differing ideas on the origins of flight in birds (the custard-coloured one being an illustration of the 'ground up' idea).

Perhaps the most strikingly Stoutian (not to mention really, really '90s) piece in the book features a gang of Deinonychus launching themselves at a herd of the considerably larger (and more recent) ceratopsian Centrosaurus, apparently without a great deal of success. It's evocative of Stout's Deinonychus v Tenontosaurus scene, except the Deinonychus aren't quite so bony and there's a great deal more silliness. I'm particularly fond of the gravity-defying Deinonychus being vaulted up into the air atop the horn of a mean-looking, sunken-faced Centrosaurus. The face-tugging Deinonychus on the right is also rather amusing, particularly as it seems to be in imminent danger of getting completely smooshed. Just check out the evil eye on the horned beastie!

'Differences' here include the individual being tossed up into the air in the background, demonstrative of how prey animals were more than capable of fighting back (and often in a variety of quite imaginative ways, it would seem).

From cross-looking ceratopsians to cross-looking (and rather pink) hadrosaurs, as Maiasaura glowers disapprovingly at a nest-raiding Troodon (with unusually long, bendy, bony arms). The grumpy-looking beak on the foreground Maiasaura rather reminds me of the Iguanodon in pretty-but-mediocre Disney CGI-a-thon Dinosaur, although there thankfully isn't a temporally misplaced lemur to be seen. Instead, a group of Pteranodon fly serenely overhead, while the foreground is invaded by a grotesque Oviraptor, depicted with its famous erroneous nose horn in true 1990s stylee. Lovely colouration, mind you.

In contrast to most of the other scenes, there's actually quite a lot of empty space in this composition, which serves to emphasise the face-off between the Troodon and Maiasaura at the centre of the image. One of the 'differences' here is that, while the Troodon is shown holding an egg on the opposite page, it has here been intimidated into dropping it. Parker points out that Troodon was positively diminutive when compared with the hefty hadrosaur, and the herbivore's sheer size would have been a potent defence in itself. Again, it's a nice way for the author to talk about dinosaurs as real animals, overturning ideas based more in old-school palaeoart tropes than reality.

And finally...it's Dinogeddon! Again! Volcanoes, poisons, egg-raiding mammal scum and asteroids! When will the madness end? For all that it's essentially a montage of different saurian extinction theories, there are, again, some great touches here. Dave Hone (from whom I borrowed this book - thanks again, Dave!) pointed out the toothed birds, which would indeed have been a reasonably common sight in the Late Cretaceous but are seldom illustrated as part of a wider fauna. In this case, they are intended to be Ichthyornis, which would be a tad anachronistic, but never mind - at least the choice of mostly black plumage is an unusual one. The horrible pustules on Rexy are also an unusual touch, although in this case they are referencing a famously Bakkerian idea about the dinosaurs' extinction (as also referred to by annoying tyke Timmy in JP). Whatever - we'll just pretend that the intention was to show that dinosaurs likely suffered various Mesozoic ailments, but this is rarely depicted in art. Tra la la. Hey, isn't Rexy's colour scheme rather dandy? You don't see that sort of washed-out grey striping very often. Another hat-tip to Dave there.

Presumably because it's the final scene, Parker and Fuge decided to have a bit of fun, and some of the 'differences' are deliberate errors. One of these is the mutant extra digit on each of Rexy's hands, although the spindly, twig-like nature of the arms is not accounted for. Another is the spear piercing Rexy's hide, thrown by a Japanese whaler who fell through an inconvenient tear in the fabric of space-time (not really). The latter genuinely is intended to evoke a pop culture trope, namely that of cavemen living alongside dinosaurs, as depicted in such movies as One Million Years BC, which might have featured an actor wearing some sort of bathing costume that's been shoehorned into a lot of articles about dinosaurs in the mainstream media.

That's quite enough rambling from me, but I'd like to reiterate that this is a quite delightful book for all its weirdness, and I only wish I'd thought of the 'science via spot-the-difference' idea first, 'cos it's quite brilliant. Coming up next time: whatever I find on eBay in the next few days!

It might just be me - and might just be the 90s - but these kind of remind me of some of Josh Kirby's book covers (notably Pratchett's Discworld).

ReplyDeleteI honestly thought those Ichthyornis were supposed to be modern-style Dinosauroids tossing spears at a T.rex. For that brief moment (until I read further) I think my heart stopped beating.

ReplyDeleteAlso the Coelurus in the background appear to be direct copies of Stout Coelophysis, as does that sickly Triceratops in the final image.

DeleteI think you're right there. Yet again, I've dropped the ball...

DeleteSo did I.

DeleteWhy did early paleoartists assume Archaeopteryx had to have been brightly colored? The idea of Archaeopteryx as a Mesozoic crow (Recently gained some new ground after SVP '14) is actually a breath of fresh air.

ReplyDeleteIt's not strictly true that they always did - there was a bit of a 'magpie Archaeopteryx' meme for a time (as noted by Darren Naish).

DeleteOh yeah I remember that.

DeleteWow...I hope I'm duly forgiven for mistaking them for being actual Stout paintings!

ReplyDeleteOh... Oh dear lord this art is wonderful. It just hits me squarely in the pleasure center. So cartoony, yet naturalistic and so lovingly rendered. You can just tell Charles Fuge was having a blast on this project. Stop being so cute, crazy Archeopteryx family, you're not even real! It's not fair to tempt me with such lurid imagery!

ReplyDeleteI remember this book when I was little. Even then it always confused me how the Ichthyornis was able to grasp and lift that little rex with those feet.

ReplyDeleteI actually like the cartoony look and colors on some of these, those turquoise-black-white Coelurus especially, although before reading I thought they were supposed to be Coelophysis. Also, I have a feeling those pink Maiasaura were inspired by flamingos, with those black beaks, colonial nesting behavior and ash-colored hatchlings. Unfortunately the combination of big blubby bodies and flesh-pink color look like they have a bad case of sunburn.

ReplyDeleteAs it happens, I own a copy of this book. And of all the wild color schemes, the one that made me groan were the Archeopteryx cosplaying as Scarlet Macaws.

ReplyDelete(Well, that and the flamingo-Maiasaura, but that's a given.)

This book looks bonkers!

ReplyDeleteIronically, the Coelurus have an advantage over most restorations in having a slender, elongate dentary (Carpenter et al., 2005), while most artists just make them a poor man's Ornitholestes.

ReplyDelete"a grotesque Oviraptor, depicted with its famous erroneous nose horn in true 1990s stylee"

ReplyDelete"erroneous"? What is THIS about??

Is "stylee" a typo or some more Brit slang?

'Erroneous' means 'in error,' basically. See: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/erroneous?s=t Unless you weren't saying that you didn't know what the word meant, in which case...Oviraptor didn't have a nose horn.

Delete'Stylee' is a humorous way of saying 'style' in that sense. See http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/stylee?s=t

I meant the latter. I kind of understood that Oviraptor didn't have an actual horn, in the sense of a rhino or ceratopsian, but the crest is still "on the books", so to say? If not, then did the fossils showing such get reassigned?

Delete