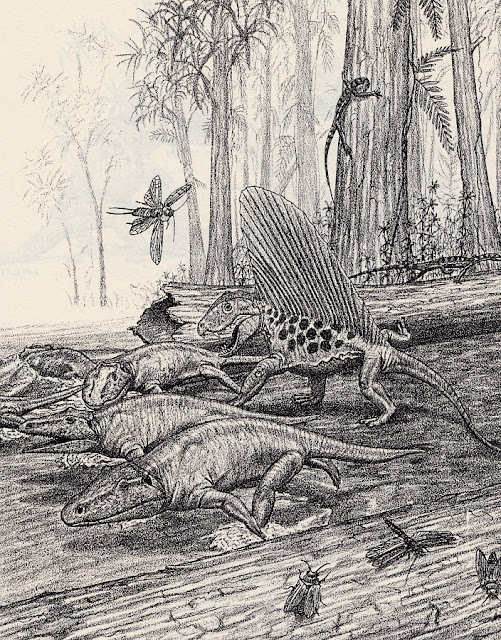

Naturally, these Permian beasties appear in a section providing the background and overall evolutionary history of theropod dinosaurs, a chapter replete with wonderful illustrations like this one. It's intriguing to see Greg Paul take on animals other than the ones we're used to seeing, and the results are predictably very lean-looking, although it's lovely to see Dimetrodon being so energetic (and definitely not marking its territory, no matter what Thomas Diehl might think over on the Fezbooks). This is also a notably richly illustrated Permian scene, with an assortment of fauna swarming over an imposing forest - as opposed to a blasted sand dune with a few generic fronds scattered here and there.

Many readers will recognise the above piece from Paul's 2010 Field Guide to Dinosaurs (second edition coming soon!). Aside from the forelimbs, it's aged rather well - Paul's style probably suits Coelophysis more than any other dinosaur (after all, it's an animal that has literally been rendered as pair of rubber-coated pipe cleaners before). Note both the Bakkerian neck plumes and mixture of 'robust' and 'gracile' morphs. It remains an exciting and energetic piece, as a marauding gang of unnervingly gangly, long-necked theropods round a bend to confront the viewer.

On to the Jurassic, and a reclining Allosaurus (Mark Witton would approve) watches Camarasaurus, Diplodocus and Stegosaurus around a watering hole. This piece is all the more effective for presenting the scene from a human's eye view, as if Paul drew it from life (which Mark notes is a very effective palaeoart technique in Rec-a-Rep). It's nicely composed, with a good variety of animal life on show (there's more than just dinosaurs here), and the context is entirely naturalistic, recalling layabout lions eyeing giant African herbivores as they gather to drink. If there's one bothersome aspect of this, it was what Niroot pointed out to me - namely, that the way the Diplodocus' tails pivot up into the air is a little strange. They're on a slope, sure, but why does the tail stick up to oppose the head and neck, like a see-saw? Wouldn't it just stick out behind, given that they have a solid quadrupedal base to stand on? Nitpicking, though - this is a fantastic piece, one of the best in the book.

As the Late Cretaceous draws in, so we are treated to rampaging tyrannosaurs making a nuisance of themselves. Again, we have a wonderful mix of herbivore behaviours. The less well-defended hadrosaurs Kritosaurus and Hypacrosaurus scatter to the left, dodging Edmontonia (just visible on the scan) which is notably less concerned. Meanwhile, the ceratopsians Chasmosaurus and Centrosaurus act like belligerent, overgrown bovids, confronting the threat and brandishing their horns. It'd be a foolish Daspletosaurus that took on such a foe. Such well considered, exciting pieces like this demonstrate why Greg Paul still deservers a place at palaeoart's top table.

Interestingly, the huge pterosaurs shown here are Quetzalcoatlus, and they're much closer to their 'modern' look than many other artists managed at the time (most of whom were, admittedly, busy copying Sibbick's nubbin-headed beast). They share the sky with modern-looking birds.

There's some other cool stuff which I haven't featured yet that doesn't appear in the aforementioned chapter (A History of Predatory Dinosaur Success and Failure, and of their Avian Descendants, should you have been wondering), so I'm going to tack it on artlessly here. Here, the frankly quite bonkers-looking Mamenchisaurus hochuanensis is confronted by Yangchuanosaurus shangyouensis, which Paul lumps into Metriacanthosaurus for some reason. One of the allosaurs has sliced some flesh from the sauropod's thigh. Intentionally or not, the two tiny pterosaurs flying past the sauropod's neck are reminiscent of old palaeoart pieces, where they were used for scale - in particular, Zallinger's The Age of Reptiles mural.

Having said that, Paul is very keen on busting old palaeoart tropes where appropriate. In Paul's own words,

"Far from trying to escape into water for safety, herbivorous dinosaurs were in dire danger if caught by packs of swimming theropods, as is the case with this Apatosaurus louisae, surrounded by Allosaurus atrox [probably just A. fragilis]."It's a classic cutaway that's been imitated many times since. Judging by the signature, it was originally drawn in 1980. One can easily imagine how revolutionary it must have seemed at that time.

When not bandying iffy taxonomy and confusing terminology about ('brontosaur' as an alternative term to 'sauropod', as opposed to referring to a particular type of sauropod? Huh?), Paul was often far ahead of everyone else in terms of the quality of his reconstructions. Anomalous vestigial finger aside, his Baryonyx (above) is much better than many others at the time, some of which sported piratical appendages on the end of their arms.

I'm sure I've said previously that I'm so very happy that ornithomimosaurs were found to have had a feathery covering. They just make so much more sense with one. Once the more jobbing dino illustrators catch on, and once tight-arse publishers stop reprinting crudely modified Sibbick illustrations from the Normanpedia (31 years young!), we'll finally be rid of the creeptastic, tiny-handed, stilt-legged, prune-skinned monstrosities of the '80s and '90s once and for all. Of course, Greg Paul got there first. GSP was right! Tell the children!

...Except, of course, he wasn't always. I'll leave you with this charming skeletal diagram, depicting a composite therizinosaur transformed into Plateosaurus-meets-Edward Scissorhands. Why would I finish a celebration of Paul's triumphs with this unfortunate guess-too-far? Because I am, in the end, a right bastard.

Next time: life-size fibreglass dinosaurs return to LITC, with guest star Dave Hone (for it is he)! Oh, yes.

It IS interesting that ornithomimids did not themselves start the Dinosaur Renaissance. I guess they were just too lizard-hipped? The creationist babble my parents used to buy for me always harped on that. (They always conveniently neglected to show the bird-hipped skeletons of dromaeosaurs though.)

ReplyDeleteI had no idea about the aquatic scene. Amazing. There is an almost identical depiction of a swimming sauropod with a pack of carnosaurs ( although an original image, not a copy ) in William Stout’s The Dinosaurs published in 1981.

ReplyDeleteIt made a big impression on me when very young as I had never considered anything like it before. To be fair it is proceeded by a very beautifully atmospheric scene of a herd of sauropods traversing a very narrow sea lashed cliff path. And it all illustrates a very dark and evocative piece of short story writing by William Service. In the end they all get horribly picked apart by pliosaurs.

So I’m guessing that this original version of the image probably inspired that whole short story sequence as soon as it had appeared.

That particular Baryonyx looks mighty familiar.

I really think G. Paul was wrong to illustrate theropods like allosaurus with "lips," because, if I'm correct, the upper teeth would have eclipsed the foramina of the lower jaw.

ReplyDeleteAllosaurus really didn't have particularly long teeth...

DeleteIt didn't? In the images I've seen, the foramina of the lower jaw are eclipsed by the upper teeth, usually; I believe this was even more of a problem for the "lips" theory for others such as dilophosaurus.

ReplyDeleteHave you ever made a post listing down all the hilariously absurd dinosaur theories yet? If not I suggest you look them up, some are as weird as fire-breathing Parasaurolophus and flying Stegosaurus. Good stuff.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete