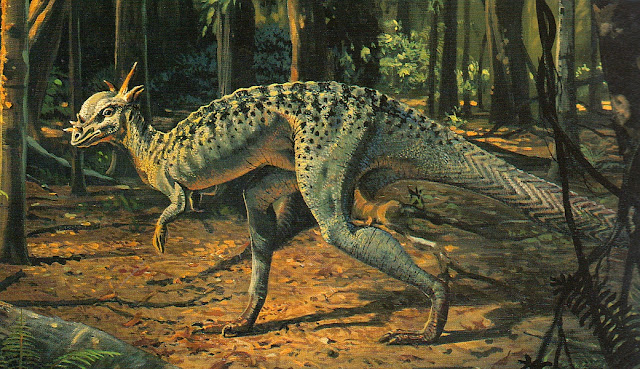

As noted last time, scanner-related limitations mean that I am forced to present mere details from some (OK, almost all) of the pieces. As such, this Stygimoloch should be imagined as part of a far wider forest scene, presenting the animal as part of an enormous and complex ecosystem, as is par for the course with Kish (and a few other artists, notably Doug Henderson). Its wonderful colour scheme (chevron tail!) demonstrates a typically Kishian affinity and aptitude for cryptic camouflage. It may appear horrendously shrink-wrapped today, but it's possible to appreciate the careful painting of the animal's hide in the dappled light, and the beautifully naturalistic appearance of its poise. It's possible to imagine stumbling upon this creature as it skulked through the forest, with the animal giving the viewer a cautious glance before continuing on its way.

A similar impression can be gleaned from this painting of 'a fabrosaur' (modeled on Scutellosaurus). It is similarly peaceful, dominated by impressive foliage and depicting an animal pausing to drink from a stream. The eye is immediately drawn to the animal in the foreground, and it's easy to let the mind fill in the blanks as regards the forested background - however, closer inspection reveals a surprisingly alien flora, as it no doubt was back in the Early Jurassic. The water here is particularly impressive, I feel (then again, I'm easily impressed by a pretty reflection).

The 'soft tissue light' approach can often produce some startling results. The animal on the right, for example, looks so radically different from the chunkier renditions that we're used to that, unless you're familiar with the skeleton, it's hard to tell what it is (I may well have said something similar about Maiasaura last time). In fact, this rather sad-looking creature is an unusually cheek-and-Deinonychus-less Tenontosaurus. Again, it may look a little emaciated, but seeing this animal without an accompanying troupe of merrily jumping dromaeosaurs is rare even today, so much so that a fairly conventional-looking John Conway Tenontosaurus simply strolling about made it into All Yesterdays. Granted, there is a theropod here, but it's a rather unthreatening Microvenator (an oviraptorosaur). Contrary to many depictions of this animal in which the focus is on blood and guts and fangs and claws and blood and fighting and blood and death, here Tenontosaurus is virtually upstaged by the glorious forest behind it. The plants will take back palaeoart, in the end!

In a similar vein, here are some Hesperornis sitting in front of a fantastically beautiful pine forest. They don't appear to be anywhere near awed enough by their surroundings. I posted this photo on Facebook, and Matthew Inabinett noted that this environment was an unusual one for these particular animals to be shown in. Indeed it is - although they are not depicted in palaeoart too frequently, these loon-like swimming birds are typically shown chasing fish in a very definitely marine habitat. However, my exhaustive research that certainly didn't consist of a cursory glance at Wikipedia confirms that Hesperornis remains have been found in freshwater formations. Once again, Kish has taken a substantial break from palaeoart convention - and all those years ago.

Kish's Triceratops piece has graced the hallowed pages of LITC before, way back when David - aged just six at the time - was the solo author. It's an older work, dating from 1975, and the animals actually appear notably less shrink-wrapped than they might have done had they been painted in the '80s. Those sprawling forelimbs are a rather unfortunate anachronism, but it's a superbly painted piece that is still uncharacteristically anatomically rigorous for the time. If I wanted to sound especially plummy, I might even call it 'splendid'. But I won't be doing that.

And finally...when I previously bloggerated about this book, I assured concerned commenter SciaticPain (lovely) that I'd comment on Russell's writing this time around. Unfortunately, I'm a filthy, lazy liar, and you should probably lock me in the stocks and pelt me with rotting fruit - for you see, I've hardly read any of the text at all. (To be fair to, er, me, these posts are mostly about the art - I'd require a whole other series for the text.) However, what I've looked at is, as SciaticPain (oh dear) rightly said, a very good read indeed. I was struck by its pertinence from the off, when Prof Dale touched upon an issue that has affected every dinosaur enthusiast, from the museum-clogging child to the wizened academic in his office filled with undergraduates' half-arsed essays:

"'Dinosaurs? They're extinct! You can't feed dinosaurs to hungry people, and there are more important things for youngsters to learn in order to prepare for life...'It is common for an interest in prehistoric life to be viewed as an irrelevant, childish frivolity. In An Odyssey In Time, Russell goes to highly impressive lengths to show that this is not so, and to tie such an interest in with a broader view of the history of life on Earth. In fact, in his closing chapters, he encompasses no less than the entire cosmos. In such a context, it seems plain mean to produce a photo of that 'Dinosauroid' thing, so of course I won't. I'm a kind and charming soul really.

Perhaps the names of those of us who could make the foregoing comment our own are legion. Why is it not the same with our children? ...They dream about dinosaurs, draw them...Dinosaurs are a touchstone that separates the mentality of children from that of adults."

Whatever you might think of Old Greeny Bug-Eyes, this is a remarkable book that deserves the utmost respect, both for Dale Russell's impassioned writing and Eleanor Kish's ground-breaking palaeoart. It's well worth searching for.

And search for it I shall. I really do want this book.

ReplyDeleteI'll trade you my copy!

DeleteOh, will you? But I've nothing suitable to trade with...

DeleteI'll get back to you at DA.

Deletei have that exact Stygimoloch postcard, and what looks like a Hypacrosaurus postcard by the same artist, above my desk AS WE SPEAK! how serendipitous!

ReplyDeleteOld Greeny Bug-Eyes and troodon companion should have had feathers. Maybe a nice feather mowhawk and pubic feathers for Greeny to go along with the silly parallel evolution speculation.

ReplyDeleteThe text in this book is still considered a classic among palaeoecologists. All the scientists I've talked to about how to recreate the environment of DPP have told me to just read this book...

ReplyDeleteAgreed - the book is a good read for all you palaeoecologists out there.

ReplyDeleteI didn't really care for it, text-wise, but that's probably b/c it wasn't what I was looking for when I got it.

ReplyDelete1stly, the 1 Customer Review for it made it sound like a dino book "for the enthusiast" ( http://whenpigsfly-returns.blogspot.com/2008/04/paleo-reading-list.html ). However, it was actually WAY more technical.

2ndly, the Book Description & Editorial Review made it sound like a book about dino biology/evolution. However, to quote Switek, it was actually "more of a list of what lived where and when than anything else" ( http://laelaps.wordpress.com/2007/07/07/what-ever-happened-to-antrodemus/ ).

To sum up, text-wise, I'm sure its good for the specialist who likes lists, but not me.

Like I said, I haven't really read very much of it, but was quite impressed by the intro and final chapters, as you can tell ;)

DeleteDon't get me wrong as I wasn't disagreeing w/what you said about the beginning/ending text. I just figured this would be a good time & place to share my thoughts on the main text. ;)

DeleteMmmmm...Dinosauroid...

ReplyDeleteThe pairing of Kish and Russell was great in some ways, but the bizarre dinosaur anatomy is irksome. I'm glad the work has such fatal flaws, because Ely Kish makes me so jealous I want to smash things.

ReplyDeleteEverybody makes me so jealous I want to smash things. Chiefly myself.

Delete